[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

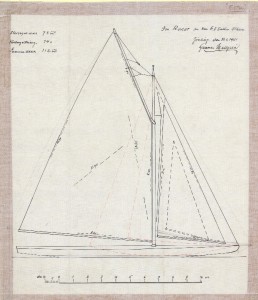

We called her the mini Vasa – after Stockholm’s famous museum ship. She is Ester, the 1901 champion racing yacht designed by Gunnar Melgren, with a dagger keel for extreme performance… and she was a Baltic racing legend. But she sank offshore in the late 1930s and seemed lost forever…

The Swedes seem good at bringing vessels out of the deep, as their Vasa museum proves, and so perhaps it was normal for Bo Eriksson and his friend Per Helgren to start dreaming of finding her again… Their second (newer) dream is now to sail her at the Mediterranean regattas.

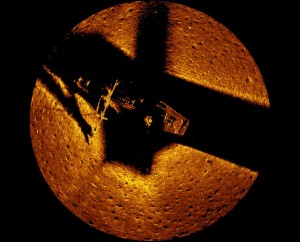

After some research Per had narrowed it down and incredibly Ester was found – intact in 165ft (50m) of water. She was raised and they have been rebuilding her. This is the story so far…

In the first magazine edition of CS, Ester was introduced to readers as the fin-keeled racing yacht, designed by Gunnar Mellgren and built by August Plym specifically to race against Finland in the Tivoli Cup of 1901, which she won. We previously read how she continued to race and win with unusual regularity from her launch, until the Great War. Her later untimely and seemingly definitive end was described in the fire aboard, shortly followed by her loss, somewhere near the Baltic town of Örnsköldsvik on the Swedish High Coast. There she lay from around 1939 until 2012, when Per Hellgren and Bo Eriksson found her on the seabed.

(Update: Ester was relaunched in August 2019 – see report and the CS original story: HERE )

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

This article, on the rebuild of Ester, describes some aspects of the project that may be unusual today, covering some technical considerations.

The sunken vessel was clearly in a very fragile state. A custom fabricated cradle was lowered from a crane mounted on a catamaran and the strops tightened around the hull. She demanded utmost care in extraction from her resting place of 80 years. Gently, she was pulled. The mud clung to her hull and sucked around her keel, holding her fast. 164 feet above, the crane continued to increase the tension that was spread along Ester’s 50 foot mahogany hull and yet, she did not move. With the scales reading 6 tonnes, air was ejected through the pipework surrounding her. This attempt to break the water seal was successful and Ester was free.

The sunken vessel was clearly in a very fragile state. A custom fabricated cradle was lowered from a crane mounted on a catamaran and the strops tightened around the hull. She demanded utmost care in extraction from her resting place of 80 years. Gently, she was pulled. The mud clung to her hull and sucked around her keel, holding her fast. 164 feet above, the crane continued to increase the tension that was spread along Ester’s 50 foot mahogany hull and yet, she did not move. With the scales reading 6 tonnes, air was ejected through the pipework surrounding her. This attempt to break the water seal was successful and Ester was free.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

Approaching the surface, the sleek plan became a vague outline beneath the slight ripples on the water. Although the identity of the boat had been confirmed by the information brought back by the divers, with the emergence of the coachroof and deck from the darkness came responsibility. Bo and Per, having waited years for the recovery of this lost champion, decided to leave her floating just below the surface. When the poor weather of the next day had abated, they returned to complete the salvage.

Ester was carefully emptied of mud and debris (including 2 sealed bottles of something intriguing) before being lifted from the water. She was then escorted by road to her temporary residence where she will stand in moulds until ready to support herself.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

Ester’s shed has a footprint of 450m2 and yet is a tardis. Inside is like a museum, boasting a 1934 twin spritsail Sneper, a 26’ open double ender, a 1919 Petterson designed 30’ gentleman’s launch, a 2.4m class boat, 2 iceboats, a Whitehall dinghy, some models and Magda IV, Bo’s 50’ gaff cutter from 1904.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

Between her launch and the great war, Ester sailed in numerous regattas. During one of these events, in 1905, she was photographed in Gothenburg sailing alongside Magda. When Ester arrived in Örnsköldsvik in 2015, she was stood next to Magda, primarily in order for all to see their reunion after two world wars and the greater part of a century… Oddly, during ester’s absence, The two have been moored less than a mile apart, albeit one below and the other above the surface of the sea.

Unfortunately for Magda, Ester seems to have taken the best spot in the hayloft this year. Within the four traditional board-on-board outer walls, are two lesser, insulated structures. One is a long, narrow machine shop and the other houses Ester. Beneath Ester’s right hip are two reverse cycle air conditioners that maintain the mild climate inside the mud floored space.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

However, when the outside temperature falls to -25 during these winter months, which it inevitably does, it is difficult to keep Ester warm. The air conditioners have to then draw heat from inside the shed to melt the ice forming on the bit outside doing the work. By leaving the lights on around the clock, what little heat is generated is enough to keep Ester and, more importantly, us from freezing.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

As well as being difficult for us to work in such low temperatures, the air has little energy to keep moisture bobbing around. So, although the relative humidity (RH) may be the same as on a warm summer’s day, the absolute amount of water vapour present in the air is much less. Consequently, when that same air is heated, in a building for example, the RH falls. This creates further complications for the work.

Whereas this ‘dry’ cold is often said to be comfortable to us, it wouldn’t be very good for Ester because it dries the wooden structure too much, contracting the fibres. A modern swedish boatyard, unlike Esters, more like Stockholms Båtsnickeri, has a concrete floor and a warmer environment. Here, they solve the problem of low RH by vapourising water through jets in the ceiling, similarly to the Eden project. This keeps the moisture content of the air high and the dimensions of the wood constant.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

In Ester’s nineteenth century hay loft in Örnsköldsvik, air humidity is controlled differently. The permeable mud floor allows water in the ground, as well as from the unplumbed sink, to evaporate into the air inside the shed. This long-standing arrangement is enough to keep the wood from distorting, albeit at a tolerable average temperature of six degrees.

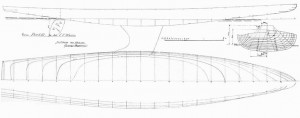

The mud floor rises and falls like the tide, though dictated by the temperature. This poses issues when stabilising the boat, as well as machinery. Ester’s structure is largely supported by the metal framework surrounding her, which is braced against any significant distortion. Her long overhangs, i.e. front and back, are braced against the building, however. The movement of the building, in relation to the boat, is monitored via a permanently mounted centre-line; a 50’ length of MIG welding wire pulled taut between the stem and stern.

The slow process of deconstructing, re-aligning and documenting began. Records were kept of everything done to or taken from the boat, including all of the measurements key to putting her back together. Horizontal and vertical datums were set and the hull manipulated to conform to Mellgren’s designed shape. With the deck off, the small team of Bo, Per, Göran and Mebrahtom (Meb) were able to asses the sheer line of the top plank.

Over the years, whether it be through hard sailing or most of the twentieth century spent underwater, the boat had suffered dramatically. Running fore and aft, the oak centre-line had a 6” bend to port. The sheer line was high amidships and incongruous elsewhere. Athwartships, the mild steel frames had for the most part disappeared and the oak ribs were all split. The mahogany hull planking varied in thickness and in places, as little as 14mm remained.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

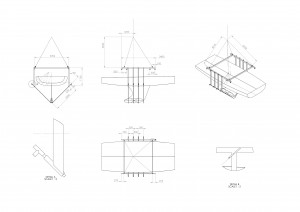

Having established the corrected shape and axis, the first challenge in reconstruction became the replacement of the steel frames and their fasteners, namely, hollow mild steel rivets. A highly skilled local metal worker was consulted and commissioned to help realise this task. Göran’s eye-wateringly precise fabrication work and innovative stainless steel hollow rivets will be illustrated and explained in the next article. We’ll look at the machinery and process employed in bending the frames, follow Malene machining the 2500 high grade stainless steel hollow rivets and consider how innovative this technology was in 1901.

The Frames

The frames are made of high quality stainless steel bought as flat plate 3mm thick. They are cut into strips and pressed into angle iron – the angle is tailored to each and every frame.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

Specific angles are required.

Then they are tag welded together and then rolled in the machine to achieve the right shape according to the hull – you can roll whatever you want in this machine – there are three wheels powered by a hydraulic system and you start slowly and then progress – it takes just ten minutes. Done by eye.

We do some manual adjustments to make it perfect of course.

The frame is then punched with the holes which are perfectly round. We have made 2,500 holes in the frames before we put them in the boat. Then they are temporarily bolted into the old planking. So when we put the new planks on we glued them in place and took out the nuts and bolts and started riveting.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

Each rivet is 8mm with a 14.5mm head (there is a 30mm hole drilled in the rivet. The rivets are not really needed for strength, they are hollow so are the same weight as a smaller rivet but their thickness makes them a much stronger fit with the frames to the planks so we can achieve more rigidity. We use air hammers to finish the rivets from the inside of the hull and outside we have a man with a dolly made of steel.

We can get a really tight solid finish. And the rivets are slightly angled at 20 degrees the underside of the head that is, so that they sit into the wood well and don’t cause any splitting. The rivets are made for us locally by a company in Ornskoldsvik called Sanco.

That is how she was made originally – we have seen rivets before but not on such an early boat. But we did find a paper from America on how to make hollow rivets from 1883 for a general applications so we know it was already being done. These are very high grade stainless steel – the originals were of galvanised iron.

The floors are of Oak and they are riveted with longer rivets onto the frames. They also have wood screws from the outside into the floors.

Then the finish is done with plugs and the hull is faired back in the normal way. There is 500mm between the steel frames, and two steam bent oak frames, 25mmm square are between each steel frame in the normal way of composite construction.

This produces a very strong hull indeed and replicates Ester’s design perfectly.

Ester is now (October 2018) almost decked and the keel is back on, and her relaunch date is planned for the spring of 2019.

The plan then is to take her south to the Mediterranean regattas to race against the likes of Bona Fide.

And she’s already creating interest before she is even out of the shed. “For instance when we contacted a company called Tinter in Gothenburg about sourcing some Awlgrip paint and varnish to use over the coming winter,” Bo says, “they got so interested in our project that they have ended sponsoring the paint and and varnish.”

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

Ester 1901

LOA: 15.3m

LWL: Beam: 3.08m

Draught: 2m with plate

Draught: 40cm sans plate

Sail Area: 108/120M2

Website for Ester: HERE[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]