When the last six working Thames sailing barges doused their canvas for the final time in 1963 it was the end of an era, but Jim Lawrence survived. Dan Houston first met him in 1999 and this interview mostly dates from that period. But while Jim had retired as a sailmaker, handing over the famous James Lawrence brand to his son-in-law in 1997, he was still involved in sailing barges and designed the rig for the Blue Mermaid . Aged 86 he was sailing a Yachting World 14 footer out of Brightlingsea with a modified lugsail rig and had recently launched a book of his life – London Light.

THE RIVERS COLNE, Blackwater, Stour and Crouch on the English Coast boast more than their fair share of sailing characters, but the name of Jim Lawrence is almost legendary in the area. It isn’t just the treasure trove of silver he’s collected in a lifetime of racing Thames sailing barges, or the successful sail loft he started – which has tailored suits for many of the world’s Tall Ships and a host of smaller (and not so much smaller) traditional and modern craft… It’s more his accidental achievements which set him apart. Namely that he spent the first 15 years of his working life on Thames sailing barges, becoming the youngest skipper in the fleet at the age of just 18 in 1951, and then was one of the last skippers of the six barges which finally ceased trading in 1963 – decades after motorised barges had first threatened the graceful, stately trade that had been the London River’s lifeblood for centuries.

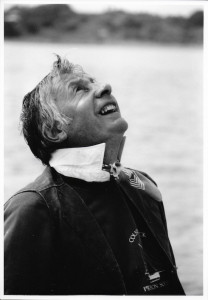

The few skippers I’ve met who learned their craft in the days of sail were awesome characters. Snowy headed, arthritic and chair-bound you half expected an arctic tern to fly from their copious white beards as they regaled you with tales from days when a Plimsoll line was a relatively modern concept. So I’m surprised, on the dock at Brightlingsea to be shaking the hand of someone who reminds me of Peter Fonda in his role for the film Easy Rider. Is it the sunglasses, or the white shirt and tan canvas waistcoat (16oz I’m told), or the lanky frame, swept hair and clean-shaven, openly impish face? I don’t know, but I’m immediately struck by the enigma of a man who basically belongs to a lost age while enjoying full nealth in the modern era. He’s 66 this month (August 1999).

The enigma vanishes in the business of getting Jim’s Aldous-of-Brightlingsea-built 1930 bawley Saxonia off the quay. Putting our mugs of tea in places where they can’t be kicked over, we sweat up the sails and use the engine to gun us out into the ebb tide. It’ll be the only time today as we’ll pick up the mooring under sail later. Jim trusts me with the helm while he squares away the cordage with three crew: Sarah, David and Ron, who at 74 has sailed with him for 40 years. We’re out on a jolly, in perfect weather, and Jim adopts the easy-going charter skipper’s air. In a rolling soft Essex burr he points out Britain’s second oldest church on East Mersea, and makes deprecatingly praiseworthy comments on Saxonia: “She’s not fast but she makes good passage times,” while at the same time checking the leading marks to see that I am keeping her in the channel and squinting aloft to see the sails are set at their best. He won’t sheet in the main or self-tacking headsail until we go about – life on the notoriously short-handed barges taught him to conserve energy. There’s a handy billy on Saxonia, but no winches.

He narrates the history of the loose-footed bawleys, and scoffs at historians who say they were not as fast as smacks. “They never raced together, so it was assumed they were slower, but we proved their speed racing with the Helen and Violet which was top boat six years running from 1979.” Helen and Violet is moored next to Saxonia, which Jim bought in 1990, removing her wheelhouse and converting her back to her original style.

Jim’s study of history is the practical, tangible approach and I get the feeling he started, with a natural curiosity, when he left his Colchester school to join Gladys, a ‘free agent’ barge that went ‘anywhere’, as her third hand on £1 a week in 1948. Learning his trade as a sailorman, as barge crew were widely known, he swiftly rose to mate, joining Falconette, of the 40-strong Colchester Barge Fleet, trading between London and the East Anglian ports. There were 150 sailing barges left then, he says. Barge hands and skippers worked on a share scheme: “Half went to the owner and the rest was divided between the crew,” he explains. “You weren’t paid to sail empty, and we often went empty up to London. But let’s say you grossed £60 for a trip. £30 went to the owner, £20 went to the skipper and £10 to the mate. The mate and skipper paid the third hand his weekly wage between them – that’s because a third man was often considered unnecessary. The owner paid for the upkeep of the barge and repairs and the crew would pay living expenses – food and bedding, coal for the stove and so on.”

Jim utters a stange strangulated cry. It sounds like: “Uhoua-houh!” The crew are ready by the foresheets and Saxonia tacks … Ah! So it meant ‘ready about’. He talks of the cargoes his old skipper carried: hay and straw for London horses in the Edwardian era. “They’d sail with 80 tons of it, stacked 14ft above the deck. The sail would be sheeted down one side of the cargo. And the downdraft of the wind would push the barge to windward.” Jim got his first skipper’s job at 18 because his skipper broke his arm hauling the barge across the dock on the dolly winch. This was on the Mirosa, now run by Pete Dodds at the Iron Wharf in Faversham. He had already learned the craft of sail-making from his old skipper, and made sails by hand in the time honoured way.

He recalls taking on a huffler, often a retired barge hand, to help get upriver to a place like Colchester using setting booms – a kind of quant pole to punt the barge under bridges up to a quay. Shooting bridges; dropping the rig to get under a bridge was occasionally dangerous. Like the time the Milly was stuck under a bridge on the Colne. She was sunk in situ by the fire brigade because otherwise she would have destroyed the bridge when the flood tide raised her. “The highest thing aboard the barge had to be the spoke of the wheel,” Jim says, bringing home just how sleek, and how slick, the operation had to be. It also called for careful loading; the wrong trim could mean getting stuck. Of course the rig had to be raised to unload and he remembers one dark night when a huffler reprimanded him for leaving his bike downriver. “He went off to get it, it was many miles to walk, but in the morning we found the bike caught up in the rigging aloft – we’d hoisted it up without realising!”

Despite a dwindling income compared to motor barge skippers Jim perservered with sailing barges until just six were left in trade. After the 112 ton Mirosa, he skippered the 125 ton Portlight and then the 147 ton Memory. “It wasn’t a case of purism, we didn’t even use the word, but we knew it was the end of a way of life and I wanted to stay with it until the last,” he says, explaining how in 1963, at 29, he was still running one of those six last working Thames sailing barges.

He breaks off his story. We’re clipping the south east shore of Mersea and it can get a bit shallow. Jim heaves the lead ahead into the sea and reads the depth from the leadline, taut but with the lead on the bottom as we pass. It shows a fathom (1.83m). Oh good, there’s plenty of water then; Saxonia only draws 5 feet (1.53 m).

The Memory was chosen as a charter vessel by the Thames Barge Preservation Society – the forerunner of much charter-based business today. After her he joined the Marjorie, and has won dozens of races with her, going back to skipper for a succession of owners. “It was a kind of camping holiday,” he remembers of early charters. “We had hammocks and Elsan toilets and we’d take people for a weekend or a fortnight. One of the highlights was sailing out to the Radio Caroline ship and tossing requests on deck in a tin, then Tony Blackburn or Johnny Walker would play them for us. We’d listen on the radio. The punters loved it.”

But chartering was seasonal and it was sailmaking that paid the bills in the winter, with Jim clearing Marjorie‘s 80ft (24.3m) hold and using his ancient foot-pedal Singer to make traditional sails for working boats being revived as yachts.

The business grew successful alongside the revival, and he took over the loft in Brightlingsea, running it with a staff of nine by 1979. He describes sail-making for barges as a constant business, and would regularly take sails in for a nip and a tuck to improve performance. He views boats’ sails much as a tailor casts a critical eye over both his and other’s suits, instinctively knowing if something is slightly out, and then analysing what has caused the fault. After 26 years in the business, he retired from sail-making in 1997, leaving the loft in the hands of his son-in-law Mark Butler. He married Pauline in 1957 and has three grown up daughters, plus grandchildren. He runs the Colne Smack Preservation Society which he helped found in 1971, and (at the time of this interview) was busy with plans to convert the redundant James and Stone wharf at Brightlingsea into new waterfrontage for the town.

This could be his biggest project yet; the town needs £1.5 million to buy the land. But as he regards it with his usual breezy air it’s easy to believe in him. “I’ve been bloody lucky in life, doing just what I wanted to do,” he says quietly.

Main Photo: Jim Lawrence on Saxonia in 1999 ©Dan Houston. Review of London Light: HERE

[…] Extract from an interview with Dan Houston, 1999Full article in Classic Sailor […]