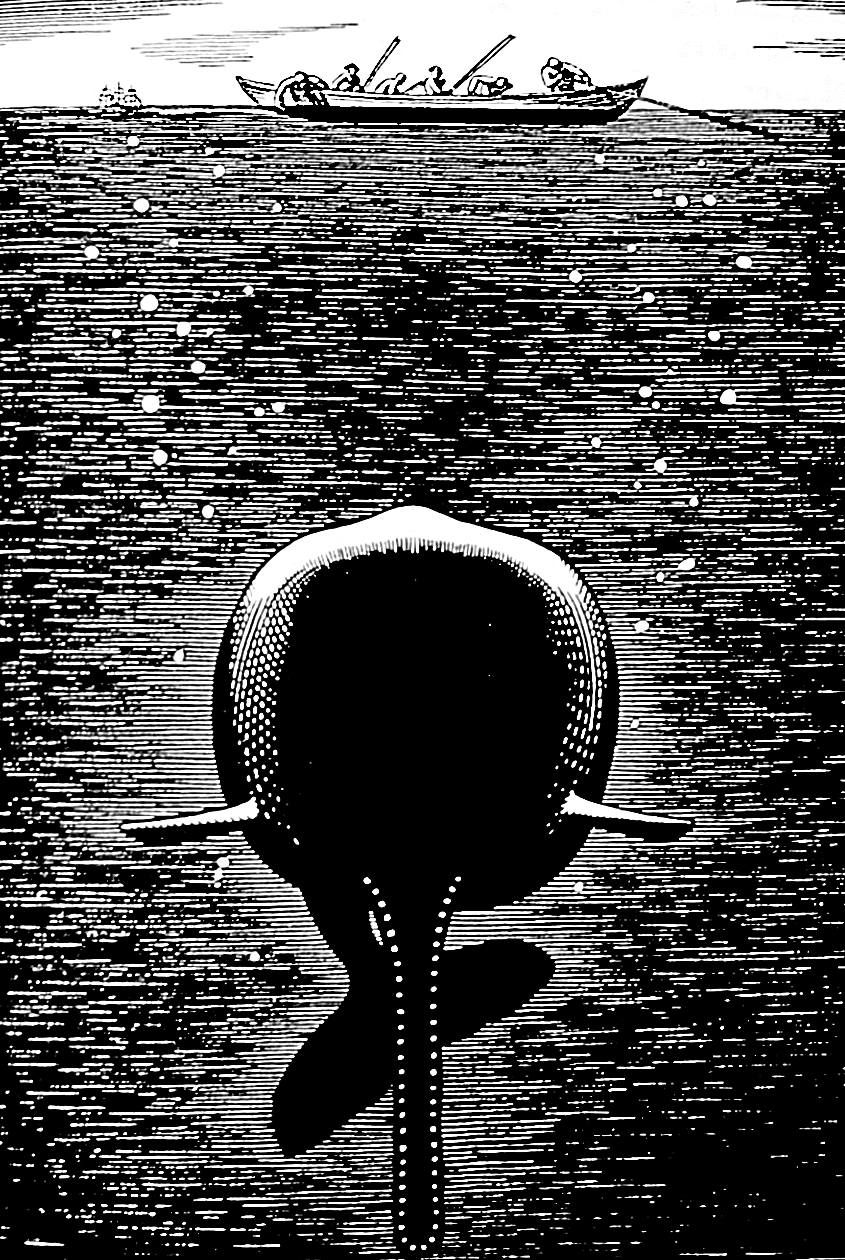

It’s often after an event at sea that you can look back with clear perspective and see things in the light of personal experience. We got caught out in a high gale in the Arctic a few years back and when I think on it now it feels like a trophy sail. The trophy sail is the one where the sea gives you something you’ll never forget. Sometimes these are the great sails, the ones where you feel suspended on the vast heaving, breathing surface of the ocean in one of its benign states; you trip out through the Needles Channel sailing down a moonbeam in a perfect night breeze, mug of hot soup in one hand and a gently thrumming tiller in the other. Or you might see dolphins cavorting around in the wavetops off Ushant, moonwalking back along a wavecrest on their tail for all the world like some smooth, shiny grey version of Michael Jackson. Or it might just be a moment in a race where the boat is hissing along with every weft and warp of her canvas drawing perfectly and she’s canted over in a winning groove.

Or, of course it’s that other kind of sail, where the sea teaches you a lesson. That was what happened in the Arctic when we were knocked down on top of such a large wave that although the sail wasn’t in the water the three foot pigs of iron ballast started to jump out of the bilges, casting aside the planks of the cabin sole.

The sea on that occasion was simply teaching us we had too much canvas up but I can still feel the tense slow motion feel of dressing to come on deck in those crucial seconds where you know you have no time to spare. Then the sensation of relief when we got the sail down with the boat’s motion settling somewhat and at last a sense of being cared for by the boat herself – the 38ft (11.5m) pilot cutter Dolphin with 100 years under her keel.

For we simply lay ahull among the breaking crests of those huge marching rollers and went to sleep in a state of exhaustion caused by nerves as much as physical tiredness; about halfway through a 450NM passage.

It was a day or so after that gale, with the Arctic in an almost placid state that I watched a black backed gull hit the water at speed and come up with a fish, most likely a saithe, which was almost as long as the gull itself. These working gulls of the wild spaces really earn their reputation – and they are large at 28 to 30 inches (71-77cm) long, weighing as much as 4.4lbs. Still I could not see how this bird was going to deal with a fish almost its own size. And yet, as we pulled alongside it had swallowed most of said fish headfirst and soon had the tail out of sight.

Then it took off in a physics-defying feat of nature, with a long, running, flapping fight to get free of the water and its wing tips splashing down for another hundred yards or so before it was finally airborne.

I feel a bit like that bird right now as we go to press with our second issue, with a few people telling us they cannot find the first one in the shops and the usual teething problems of setting up something new and becoming accepted.

But we’ve had a busy launch month, being at the Southampton Boat Show for ten days (p11), setting up our stall at Maldon (p24) and creating a magazine with a broad outlook from a whole host of experts passing on their hard-won knowledge. Add to that that we are to be distributed in America already and the month has had its own trophy feel!

I do hope that Classic Sailor is a purely positive influence on our readers as we try to share the excellent knowledge and thoughts of our writers on a wide range of traditional sailing subjects.

Do tell us about your own trophy sail! DH

Image: Suspended on the vast heaving, breathing surface of the ocean; Leviathan by Rockwell Kent