Horatio Nelson: The making of a seaman

Dan Houston charts the career that began as a 12-year-old Midshipman in 1771 and ended at Trafalgar, 34 years later

It seems almost brutal to us now that children aged 12 or sometimes even younger could be sent to sea in a first rate man of war. These wooden walled ships would have three decks with 100 or more cannon – each of which would require a gun crew of up to 14 men. The heavy 32-pounder guns of the lower deck would weigh around three tons and required heavy manpower.

The 230ft (70m) long first rates would have a crew of 850 and often marines or soldiers swelling their numbers between decks to more than 1,000. Conditions were tough and life was governed by a harsh level of discipline.

Horatio, or Horace, Nelson as he was known when young, joined a third rate – 64-gun 160ft (49m) ship when he was 12 in March 1771, with the rank of Midshipman serving under his uncle Maurice Suckling. HMS Raisonnable was newly built at Chatham but she was tasked for guard duty in the lower Thames. Within months Suckling transferred to the 74-gun HMS Triumph, taking Nelson with him. However as she was also a guardship and Nelson wanted adventure, his uncle sent him off to the West Indies in July that year, on a merchant ship – the Mary Ann.

Nelson, who had already witnessed two floggings of men tied to the gratings, was impressed with the merchant navy where ships were handled with a bare minimum of crew.

He returned to the Triumph 14 months later having crossed the Atlantic twice and with a long pigtail. His physique had improved and he described himself as a practical seaman, having learned the basics of his trade in the best school; at sea.

Suckling now gave him command of the ship’s cutter, used to ferry stores, men and orders from ship to shore. And if Nelson did well at his navigation classes he could take the cutter and even the decked ship’s longboat off on these duties. Over the winter of 1772 aged just 14 Nelson was becoming a practised pilot of the River Thames, from the Pool of London down to the tricky shifting sands of the submerged delta. It was the same school to which Drake and Captain James Cook were apprenticed, and it’s where sailors learn that the tide is king. “By degrees,” he wrote later, “I became confident of myself amongst rocks and sands, which at many times has been of great comfort to me.”

When summer arrived Nelson was again allowed to leave his uncle and join a two-ship research expedition to the Arctic, aboard the Carcass as ship’s coxswain. His fearless spirit was confirmed when, north of Spitsbergen he and a friend slipped off in a boat to shoot a polar bear. When his musket misfired he is described as preparing to attack the bear with the rifle butt, before the ship’s cannon was fired to scare the animal away.

Later, with the ships trapped in ice, the men had to saw through it to effect their escape.

Nelson’s next adventure was again as a non-commissioned crew, effectively as AB, aboard HMS Seahorse, a 24-gun sixth rate frigate. In her Nelson sailed east and visited many ports in the cruise. He was soon made midshipman but it was during this cruise that he became ill with a fever that nearly killed him. From being “a fine physical specimen” this illness temporarily paralysed him and he would never again shake off its effects. He was sent home “almost a skeleton” in his cot. Fighting depression in the valley of the shadow he found “a sudden glow of patriotism” and resolved to: “be a hero, confiding in Providence I will brave every danger.”

JMW Turner’s 1822 painting of the battle of Trafalgar, the climax of Nelson’s career, and his life. It hangs in the National Maritime Museum Greenwich, London.

Main image: The most famous portrait of Nelson by Lemuel Francis Abbott was made just after Nelson lost his arm in a disastrous raid on Tenerife in 1797. It currently hangs in 10 Downing Street, London

During his eastern cruise Nelson had familiarised himself with the challenging lunar distance system of navigation, and on his return to Britain soon found himself as acting Lieutentant aboard the 64-gun HMS Worcester bound for Gibraltar. He was given command of a watch and Captain Robinson said that he felt as easy when the 17-year-old was upon the deck as with any officer on his ship.

In April 1777, five months short of his 19th birthday he went to London for his Lieutenant’s exam with testimonials from his various captains that he could splice, knot, reef and sail and was qualified in his duties as an Able Seaman and Midshipman. During his exam his relationship to his uncle Maurice Suckling who was present and had by now become comptroller of the navy, was not mentioned and only after the quick-fire questions had been satisfactorily answered did it become known. “I did not wish the younker to be favoured,” the august Suckling remarked. “I was convinced he would pass a good exam. And as you see I have not been disappointed.”

Nelson boards the longboat of HMS Lowestoffe in a gale in November 1777 to take an American prize. The prize was waterlogged and the longboat went in on her decks and out again with the scud. In this painting the 19-year-old is telling his captain and other officers: “It is my turn now, and if I come back it is yours.” He admitted that he was often seasick in rough weather but he clearly got over it quite quickly

The very next day Nelson received his King’s commission, as second lieutenant on HMS Lowestoffe, a frigate tasked with blockade duties in the West Indies. He already had 45,000 sea miles logged, knew the life of the merchant navy as well as the Royal and knew the life before the mast as well as he did the quarterdeck. Illness had knocked him back physically but those who knew Nelson always mention his presence and radiant spirit. He came from a line of spiritual people; his father was the rector at Burnham Thorpe, Norfolk, both grandfathers were East Anglian clergy, and two great-uncles, eight cousins and two of his brothers took holy orders.

Nelson was not notably religious but this spirit, combined with his study of navigation, knowledge of practical seamanship and a deep understanding of the lot of the common seaman in the Georgian Navy had already all played a part in creating an extremely capable sea officer. He soon proved himself on the Lowestoffe, boarding a prize in the longboat in a gale where the ship’s first lieutenant had deemed it too dangerous (see Richard Westall’s painting right). He was given a schooner Little Lucy as reward and spent the winter months at sea making himself “complete pilot of all the passages through the islands north of Hispaniola” (Haiti/Dominican Republic).

He was made post captain, of the 28 gun frigate Hinchinbroke at the age of 20 – the youngest captain in the Navy.

Nelson’s early auspicious start did not herald an unbroken glittering career. A siege of Spanish territories in 1780 was a disaster with many men on the Hinchinbroke dying of dysentery or malaria. Nelson was invalided home. Nor did he escape being unemployed – the common condition of many captains in peacetime of being on half pay. He had five years of that from 1788 to 1793.

His real glory years began in 1797 where, as commodore aboard HMS Captain, he was able to take two large Spanish prizes at the same time in the Battle of Cape St Vincent. The move was called Nelson’s Patent Bridge and properly began his wider legend as a commander. He was feted and promoted to Rear Admiral of the Blue.

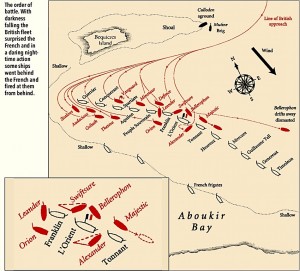

The next year at the Battle of the Nile, Nelson was in command attacking the French fleet in Aboukir Bay, in Egypt. The French had anchored confident of the shoal water behind them but they had not reckoned with Nelson’s seamanship. With a tidal range of less than 12 inches (300mm) several of his 13 ships of the line were able to sail behind the French fleet, some of whose land-facing gunports were cluttered with lumber.

Nelson combined a study of

seamanship with a patriotic

zeal which set him apart

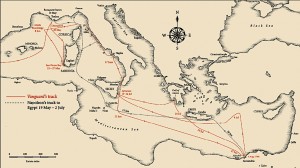

Nelson, aboard HMS Vanguard chased the French fleet around the Med before finding them anchored in Aboukir Bay

At 1730 hrs the French never thought they’d be attacked but Nelson noticed the wind direction was in line with the 13 French ships. He had directed his captains to anchor by the stern, just ahead or abaft of a Frenchman and then to pass a bowspring to attach to the anchor cable so that they could winch themselves across the wind and rake the enemy ships lengthwise. It was remarkable seamanship and several captains brought it off perfectly. Two of the most remarkable were Captains Alexander Ball and Benjamin Hallowell, on HMS Alexander and Swiftsure respectively who both anchored, in darkness, by the stern at either end of the massive French flagship L’Orient. They were so perfectly angled that they were out of the arc of the French guns yet so near that Alexander’s officers could throw fire-bomb bottles through Orient’s stern windows. She caught fire and at 10pm her magazine exploded with a blast that was heard ten miles away (in Rashid). More than 1,000 crew died instantly and the blast carried debris out and over the British ships over a 500m arc. There followed several minutes of eerie silence before fighting resumed.

These devastating tactics meant two French ships of the line and two frigates were destroyed and nine were captured. And it was down to British nerve and superior seamanship. One of the four French ships to escape was Guillaume Tell with Admiral Villeneuve aboard. He had the bad luck to meet Nelson again at the Battle of Trafalgar seven years later.

These devastating tactics meant two French ships of the line and two frigates were destroyed and nine were captured. And it was down to British nerve and superior seamanship. One of the four French ships to escape was Guillaume Tell with Admiral Villeneuve aboard. He had the bad luck to meet Nelson again at the Battle of Trafalgar seven years later.

Nelson again used anchoring by the stern as a tactic at the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, with less decisive results. The night before that battle he used the hired armed lugger Lark to reconoitre the defences around Copenhagen. Using fore and aft lug rig would be much more handy for the task, and she could make to windward under sail.

The Battle of the Nile painted by Philip James de Loutherbourg shows the moment the L’Orient blows up. Currently hanging at Tate Britain

Nelson’s awareness of the forces of tide, weather and depth of water all helped him as the consummate fighting sailor of his era. And he was promoted commander in chief of the Baltic Fleet after his success at Copenhagen.

Four years later in October 1805 Nelson was the most famous sailor in the world, and in command of the fleet aboard the first rate HMS Victory, hoping to engage a superior French-Spanish fleet of 33 ships compared to his 27. Using the weather guage – with the wind behind them – he split his own fleet into two lines which then cut the Franco-Spanish fleet into three, allowing the British to surround the central section with the French flagship Bucentaure.

Just over an hour after the battle commenced Nelson was shot from above by a French sniper and carried below, where he lay dying until he heard of the British victory at 3.30pm. Ever the sailor, and aware of an imminent gale he implored the Victory’s Captain: “Anchor Hardy, anchor! For if I live I’ll anchor.”

Nelson was concerned for his fleet and the British prizes and knew the safest option would be to anchor. It did not happen and all but four of the 19 prizes were lost. However Nelson’s naval genius and seamanship remain famous to this day.

Nelson through the years, l-r, when he became a lieutenant by John Francis Rigaud; in civilian dress 1800, by Friedrich Fuger; three years before Trafalgar, by John Hoppner; as Vice Admiral of the White with his famous eye shade, by Arthur William Devis

Horatio Nelson 29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805

Read how Nelson was brought home to England: HERE

The five-page article was in our February-March issue 2017 (No14).

You can read the rest of the magazine online: HERE

https://classicsailor.com/2019/04/read-our-back-issues/