What there is now is what I would call absolute forecasting… but keep watching the visual signs if you don’t want to get caught out

By Andrew Bray

In mid-November I decided to go out for the final sail of the season. The plan was to sail for a couple of hours to air the sails, then to come back, strip them off and bag them up for the winter. As it happens, had I gone for a sail then not only would the sails have received a good airing, they would also have had a very powerful jet wash and blow dry. This was on 18 November and if you recall, this was the day of Angus, the first named storm of the year.

Fortunately, the friend who was coming to sail with me and to give a hand removing the sails – which is not a simple matter with a gaff mainsail, was badly delayed in traffic. I say fortunately because by the time he arrived the previously

autumnal blue sky was being blotted out by omin- ous black clouds, one almost forming a vortex over the harbour. Sailing was abandoned and before the deluge arrived we managed to flake and stow the mizzen; lower, flake and bag the jib, and, once freed off its multiple lashings, bundle the mainsail down below just seconds before the deluge arrived. And, as anyone who was on the South Coast on 18 November will tell you, arrive it did in no uncertain way.

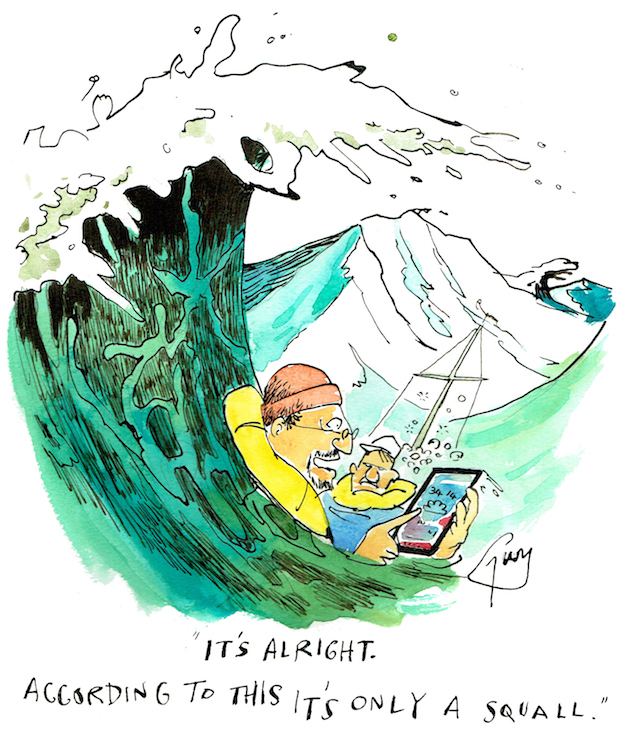

The point of this tale is to illustrate the way that forecasting, and nowcasting, has changed. You don’t have the uncertain isobar plotting from Shipping Forecasts, standing with your back to the wind to ascertain where the low pressure area is and you don’t have fishermen’s rhymes and warnings. What there is now is what I would call absolute forecasting. There’s even one app that will tell you exactly how long it’ll be before the rain arrives. That is one I didn’t believe until I tried it and you know what? The pitter patter on the coachroof was bang on time.

On 18 November, because the weather was looking uncertain, I checked the early morning

forecasts. I normally check three of them, myweather2, XC Weather and the Met Office land and sea forecasts, whilst for nowcasting I check Chimet, which gives conditions on Chichester Bar, at Camber and at a few other locations. On that morning two of the three, XC and Met Office showed a window of good weather for a few hours in the morning and early afternoon. Only myweather2 indicated that it might be otherwise. By mid morning all three conspired to agree by which time, had I been sailing, things would, as they say, have been getting interesting.

How lucky we are today to have so many sources of reliable marine weather forecasting. Even in mid-ocean, if you have Iridium or other satellite communications systems you can download grib files to give you good synoptic data and weather information which can be useful, if not vital for strategic passage planning. It wasn’t always so.

The rule of thumb used to be for those living in the UK that the further east you lived, the more accurate the forecast on the premise that it had shone, rained or blown on someone else before it arrived over you. Once in the open ocean you had no such luxury. And it was out sailing away from forecasting areas – and forecasts, come to that – that I learned more about meteorology than I had in many hours of shore-based study.

In the open ocean the sailor experiences ‘pure’ weather in that it is unaffected by land masses. He or she only has the most basic tools, a barometer,

sea and air temperature and the skills of the single observer forecaster. He or she will quickly learn that there is no such thing as a simple weather system, whether cyclone or anticyclone, but instead mini systems within bigger systems, maybe just a few miles across, that can affect the overall pattern. The observation of clouds, wind direction and a host of other signs, all add up as powerful tools in the forecaster’s armoury. Reeds used to have a useful section on single observer forecasting. It also told you about mackerel skies and mare’s tails, about the sea hog jumping and about the wind moving against the sun: archaic or just as useful today?

The danger of having instant and accurate fore- casts is that you start to believe them, which means that unless you’re also watching the visual signs, tapping the barometer if you want, one day you’re going to get badly caught out as I so nearly was.

Illustration: Guy Venables