This poem, by Robert Louis Stevenson, was published in 1888 when the author and poet was in his 38th year. RLS was steeped in the ways of the sea – he belonged to the famous Scottish Stevenson lighthouse family and voyaged in the Pacific in later life. The poem is written well into the age of the steamship but describes in detail how a square rigged sailing ship has become embayed between two headlands, and can’t make to windward to escape.

All day her crew tacks her back and forth – at times so close to land they believe they can even smell the Christmas dinners cooking in the clifftop houses.

It’s a vibrant poem that describes the humble sailor’s lot perfectly as he encounters one of the most dangerous situations for a sailing ship: to be pinned to a lee shore, until her captain risks all by putting on extra sails as night begins to fall… and they escape.

Stevenson also captures perfectly the pathos of the sailor leaving home in this poem; he can even see the house where he was born – where his aging parents are lamenting a Christmas spent without a son, a foolish son he surmises… who is away from home, at sea.

The sheets were frozen hard, and they cut the naked hand;

The decks were like a slide, where a seaman scarce could stand;

The wind was a nor’wester, blowing squally off the sea;

And cliffs and spouting breakers were the only things a-lee.

They heard the surf a-roaring before the break of day;

But ’twas only with the peep of light we saw how ill we lay.

We tumbled every hand on deck instanter, with a shout,

And we gave her the maintops’l, and stood by to go about.

All day we tacked and tacked between the South Head and the North;

All day we hauled the frozen sheets, and got no further forth;

All day as cold as charity, in bitter pain and dread,

For very life and nature we tacked from head to head.

We gave the South a wider berth, for there the tide race roared;

But every tack we made we brought the North Head close aboard:

So’s we saw the cliffs and houses, and the breakers running high,

And the coastguard in his garden, with his glass against his eye.

The frost was on the village roofs as white as ocean foam;

The good red fires were burning bright in every ‘long-shore home;

The windows sparkled clear, and the chimneys volleyed out;

And I vow we sniffed the victuals as the vessel went about.

The bells upon the church were rung with a mighty jovial cheer;

For it’s just that I should tell you how (of all days in the year)

This day of our adversity was blessèd Christmas morn,

And the house above the coastguard’s was the house where I was born.

O well I saw the pleasant room, the pleasant faces there,

My mother’s silver spectacles, my father’s silver hair;

And well I saw the firelight, like a flight of homely elves,

Go dancing round the china plates that stand upon the shelves.

And well I knew the talk they had, the talk that was of me,

Of the shadow on the household and the son that went to sea;

And O the wicked fool I seemed, in every kind of way,

To be here and hauling frozen ropes on blessèd Christmas Day.

They lit the high sea-light, and the dark began to fall.

‘All hands to loose top gallant sails,’ I heard the captain call.

‘By the Lord, she’ll never stand it,’ our first mate, Jackson, cried.

… ‘It’s the one way or the other, Mr. Jackson,’ he replied.

She staggered to her bearings, but the sails were new and good,

And the ship smelt up to windward just as though she understood.

As the winter’s day was ending, in the entry of the night,

We cleared the weary headland, and passed below the light.

And they heaved a mighty breath, every soul on board but me,

As they saw her nose again pointing handsome out to sea;

But all that I could think of, in the darkness and the cold,

Was just that I was leaving home and my folks were growing old.

Robert Louis Stevenson 1850 – 1894

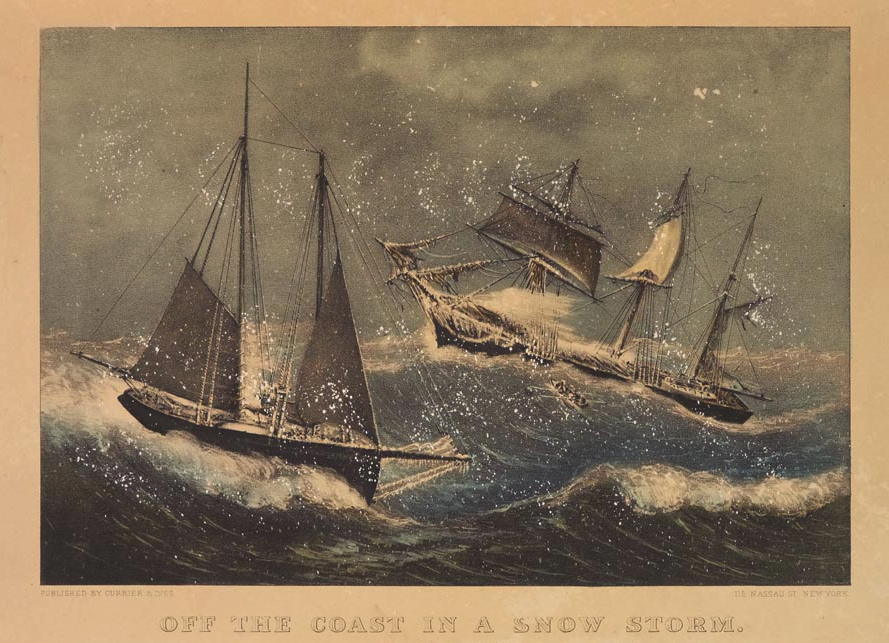

Image: Off the Coast in a Snow Storm – Taking a Pilot, published by Currier & Ives (undated)

This shows a well reefed pilot schooner sending a gig with a pilot out to a clipper,

with ice on her decks, hove-to with her main topsail aback.

From Springfield, D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts