The replica of an 18th-century lugger now sustainably carries cargo

Grayhound, the replica of a three-masted revenue cutter from the 18th century was built by Marcus and Freya Pomeroy- Rowden in Cornwall in 2010-2012 initially to offer charter sailing. But over the last three years they have evolved a more ambitious hybrid programme involving cargo deliveries under sail combined with paid-for crewing.

Here Freya Pomeroy-Rowden talks about how it all works, while later Robert Simper gives a background to the history of lug rig.

How did the idea of trading under sail come about? What was your inspiration?

When Marcus and I were thinking of the project ahead, of building or restoring a boat, we had the idea of a cargo ship. We had heard of one in the Pacific sailing flour between the islands. But we had to make the business work in Europe and we had agents – Classic Sailing – onboard from the start who were keen to promote us as a charter vessel, we knew this would work and so we built her as a Category 0 sailing passenger ship for ocean sailing.

Did you envisage Grayhound as a cargo vessel when you built her?

When we were building her we were excited about sailing her to the Caribbean and beyond and about putting our own stamp on the charter business, opening it up to families and young professionals.

Where do you carry the cargo? What is your capacity?

We can carry 4.5 tonnes of cargo in the main saloon and 2 barrels on deck (750kg)

What kind of products do you ship?

Bottled ale and wine mainly, on deck, we also age Whiskey and wine at sea. We have transported tea and honey and furniture.

Who owns the cargo?

The broker.

Where do you ship to?

Up to now, we have shipped tea from the Azores to France. We run a regular cross channel service between Dartmouth, Plymouth and Falmouth to Douarnenez. We sail annually between Douarnenez and Nantes.

How does the weather affect you? How do you keep to deadlines?

The weather always affects our game plan. We offer a seven-night cargo voyage and in that time we must make a 30-hour passage to Brittany. So in the time frame we have we make a passage plan to cross when the wind allows and the rest of the time is spent loading/offloading and sailing between Cornwall or Brittany. Both coasts offer so many places to anchor.

How important is it to customers to have a low carbon cost/footprint for their goods?

Yes it is incredibly important for the buyers, but also for the whole supply chain. Sail cargo is about the ships and routes but it is also about the supplier, the broker, the sailors, the buyers and then the end customers. It is important that the suppliers and their products are chosen well and that the whole process is fairly traded. It is trying to improve a system or a relationship between all parties. The marketing benefits for each party are huge because of the positive PR.

How do you work that out? Is it an ‘industry standard?’

Guillaume from TOWT works out the carbon saving on each cargo delivery. He previously worked for large logistics companies evaluating carbon footprints and he applies the same methods to sail cargo.

Who are TOWT?

Trans Oceanic Wind Transport. Guillaume and Diana and their four employees. They are a sail cargo brokerage and seller of sail cargo products. They are based in Douarnenez, Brittany, where they have a shop and office. They work with about six vessels and work internationally.

How many crew do you need for an average trip?

We have six permanent crew (including our five-year old son) and eight guest crew – that would be a full ship. We can sail the ship with just the permanent crew if needs be, but we really do need the voyage crew to work with us, especially with sail handling and steering.

How can you make it pay?

This is an interesting question and each boat is very different. Speaking for us, we make it pay because we built the boat to start with. We run the business ourselves and do nearly all maintenance/ labour costs ourselves in the winter months and all administration. During the summer, Marcus and I are 50% of the permanent crew and we hold all the necessary tickets. We offer our watch leader and deckhand positions solid, traditional training and experience and in return they volunteer their time. We get paid per mile to carry the cargo, which often works out as the equivalent of one paying berth per week. The cargo voyage crew pay a fee to sail with us. We also offer sailing adventure holidays to and from the Isles of Scilly and day sails during the summer months. We do not turn over a huge amount of money from our business annually and we look at the balance constantly between life quality and time off and how much money we need to cover costs, pay ourselves a living and keep the boat in good order.

How long do trainees stay for?

Voyage crew on a cargo voyage can stay for one week or two weeks. On the cross-channel we offer a discount if they book both crossings. We also offer a long-term tariff for those who want to stay for a minimum one month and this can then be extended. Our permanent crew stay for the whole season.

What qualifications apart from sea time do they work towards?

Voyage crew are there for a working sailing holiday in general. They come to experience real all-weather sailing, to learn how the traditional rig works and to learn some basic maintenance and navigation along the way. We don’t believe necessarily in qualifications, we believe in learning through doing and experiencing. Our permanent crew are all training for their yachtmaster and future jobs in the sailing industry.

How do you market the idea of crewing for paying “guests”?

What ever voyage you come on, on Grayhound, whether it be an Isle of Scilly voyage or a cross channel cargo or a daysail we expect our paying “guest” or we prefer the term “voyage crew”, to get fully involved. Everybody hoists sails and pulls ropes, steers and rows the gigs. We are not one of these charter boats where we are at anchor at 5pm and the gin and tonic is out and people can do as much or as little as they like. We are more like a sail training boat but with good food and comfortable dry bunks! We believe in the team. We need the team whatever voyage. So to enjoy a voyage with us you have to be relatively fit and in good health, be up for physical graft and like being with other people. It’s about being adventurous and open and sociable. People seem to get it , we tend to get the right kind of people. Having our son onboard also attracts the right sort of people – families and people who want to come to a family boat.

Is there an age limit on the kind of crew you are looking for?

We need most of all team players. We do have an age limit of 60 on the cargo voyages. This is not a definite rule but if our customers are over 60 we like to have a phone conversation with them to discuss the voyage and if it suits.

How important is a passion for an 18th-century sailing style, to you, and crew?

Very important, it’s why we do it. We have a simple beautiful rig which works for sailing with a group of people. If it breaks we can fix it, we built it so we know and are learning how to perfect it. It is a massive part of our heritage and history and something it’s modern boats cannot necessarily replace or improve .

What kind of concessions to modernity are there on Grayhound? (EG modern rope?)

We have no hydraulics, no outboards, no winches. Rope wise it’s quite modern but you would never know as it has a traditional look, we use poly hemp rope throughout and our sails are dacron which is new for this year. We have a 90 hp engine to aid us in calms and getting into and out of harbour. It’s very handy! We have modern navigation aids and safety equipment, of course being a MCA coded vessel. We have hot pressurised water for washing up, a shower (although this is rationed and we’re very strict with it for the shower). We have a water maker for ocean passages.

How long have you been running? How many voyages so far?

Grayhound has been sailing for four summer seasons since 2013 in the West Country and including a winter season transatlantic voyage and Carribean season. The cargo voyages have been running for two seasons. That is approx 25 cargo voyages – with about 20 tonnes carried in the first year and 25 tonnes last year.

Is there a growing market?

Yes, slowly but with root strength.

What is the ideal ship for this work?

At the moment traditional ships make the most sense because they are romantic and it harks back to an old way of doing things. But our view is that in the future, purpose built steel vessels linking smaller traditional and forgotten ports trading local products locally is the way forward.

So where next?

To grow this industry we need more end buyers and more trainees on the ships. So we’d like to mention that to any potential wine buyers, in the UK for example who might take note or potential trainees might want to book a voyage!

Contact www.grayhoundluggersailing.co.uk

Its evolution as the rig of choice for smugglers demonstrates the superiority of the lugger, writes Robert Simper

Thirty-five years ago I restored my first dipping lugger, Pet. At the time there were only about four other dipping luggers sailing in the British Isles. I got to know a little of the ways of luggers, and apart from having to dip the lug when you change tacks, this is a very simple and highly effective rig. As there is not a lot of complicated rigging they are easier to handle in the dark.

The luggers, two and three masted, appear to have developed from square sailed craft. To try and get them to sail closer to wind they tilted the yards until they produced a lugsail. The driving power of a square sail, and a taut leading edge allows them to sail closer to the wind. This was very important for coastal craft trying to keep off lee shores and rocky headlands.

The three-masted luggers seem to have first appeared in the English Channel as tubby fishing boats. These three-masters were used in the drift-net fishing because the main mast could be lowered to reduce the rolling and windage when the nets were down. The mizzen was kept set to push the bow up in to the wind. Possibly the earliest depiction of a three masted herring lugger is on the front of the 1702 Fishermen’s Almshouse at Great Yarmouth. These luggers had a jib and only set a topsail on the main mast. Following the fashion of the time the mainmast was raked aft and the topmast was stepped of the after side of the mast. The painting in the Time & Tide Museum at Great Yarmouth of the herring lugger Dairy Maid of 1851 shows a very similar clinker hulled three-masted lugger, but she has much finer lines with more sail area and a topsail on the mizzen.

In the 1970s I used to go and talk to the retired fishermen in the Fishermen’s Mission at Lowestoft. They were all very busy playing cards, but many were happy to chat about their early days in sailing smacks. One man was well over 90 and was very proud of being the last man alive who had sailed in a Lowestoft ‘lugger.’ However by the time he went to sea the three masters had long gone and a ‘lugger’ was the term for a gaff ketch with a loose-footed mains’l.

Before our highly documented society, the Government’s only way to raise money was by imposing a tax on luxury goods. Enterprising men saw a way around this and smuggling became a major industry in just about every coast in the British Isles. Since many of the crew on smuggling craft were fishermen they devised a three masted lugger that could outsail the Revenue Cutters.

The profits in the late 18th century were so high that the smugglers could afford to build fast craft and the three-masted lugger became their chosen craft. All the sails and rigging were made of natural fibre which stretched, but the smugglers had large crews to unload their cargoes quickly and with their capstan could get the halliards and sheets in bar tight, and make quick sail changes and haul the sail edges in really tight. The gaff Revenue Cutters had to be versatile craft, because they had to stay at sea in all weathers hoping to spot a smuggling craft. The luggers just made a straight dash to the beach or cove where they were going to discharge their cargo. When pursued the smugglers hardened their sheets to get up to windward and hopefully leave the Revenue Cutters astern. The Revenue men’s only hope was to get close and try and dismast the smugglers with canon fire.

The smuggling era was a strange one because no one disguised the fact that these fast sailers were built for smuggling. The Customs men knew exactly which they were and who owned and manned them, but they had to catch them with smuggled goods aboard to make an arrest. Even when the smugglers went to jail they were often bought out and many went straight back to their lucrative ‘free trade.’

Smuggling created a cross pollination of ideas between France and England and the fast smugglers luggers were the result of this. By about 1830 the smugglers were on the losing side, and their craft were of little practical use and just melted away in Britain. The French continued with three masters, with the ‘chasse-maree’, literally the fish chasers that developed into standing luggers and the result was the now famous Brittany bisquines, the fast and highly manoeuvrable oyster dredgers. Anyone who has seen the bisquine replica Cancalaise tacking in and out of a harbour can only be impressed by her handling ability and sheer beauty.

The British fishermen went on with the three-masted luggers for about twenty years, then left their ‘main masts’ ashore and continued with two-masted luggers until engines came in. However the memory of the speed of lugger lived on and in 1855 Lord Willoughby De Eresby had John Tutt at Hastings build him the 134ft three masted lugger New Moon as his yacht.

The New Moon had a single lugsail on each mast, and a bowsprit jib to balance her. She was recorded as sailing at 13 knots while racing in Tor Bay and in a race from the Thames to Harwich she easily out sailed all the other yachts.

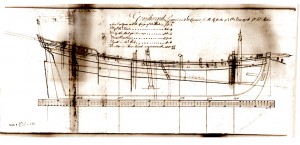

In about 2004, we made the pilgrimage up the steep hill in East Looe Cornwall to have cup of tea with Paul and Maggie Greenwood. We talked about luggers, what else! Paul got out the plans he had found in the National Maritime Museum of two 18th-century three-masted luggers, one with a large clinker hull, and a smaller 76ft carvel hull that had been built on the sand at Cawsand. Smuggling luggers had been built regularly at Cawsand, but the 76ft Grayhound had actually been built as a revenue craft to catch smugglers and went on to be a privateer. We both agreed that the 18th-century smugglers knew how to build a very fast sailing craft.

Other people saw those plans and were inspired by them, but it was the ever energetic Marcus Rawden, who took the plunge and started building a replica of the 1770s Grayhound. Marcus and Freya’s Grayhound, took shape at Millbrook in east Cornwall, and is slightly smaller than the original but is still an eye catching craft.

After her spectacular launch in 2012 the 67ft Grayhound has lived up to the reputation of her predecessor. In her first season under three lower courses she made 8 knots beating to windward in a big sea. On passage Grayhound has covered 180 mile in a 24-hour period and has touched 14.5 knots under sail. In her first four years she made two crossings to the West Indies and in four years has sailed well over 45,000 miles. Setting three sails on two of masts requires an able crew and her deck work is reminiscent of a square-rigger with endless halliards and sheets. Some of the simplicity of the two masted luggers has been lost, but in speed little can touch her.

Grayhound’s Canon

Most people associate the Grayhound with Marcus’ enthusiasm for firing a canon. The crews on the craft under fire always look a bit worried, but although no actual canon ball is used, there is an impressive explosion and smoke. The original canons were home made, but the yacht club at Millbrook, presented Marcus with two 1862 Admiralty canons that were dredged up in St John’s Lake just down the creek from Millbrook.

This article appeared in the February-March 2017 edition of Classic Sailor