A wild night and a kicking gaff caused the loss of France’s greatest sailor, on his way to the first Fife Regatta

It’s 20 years ago since France’s greatest sailor Eric Tabarly was lost overboard from his beloved 57ft 1898 Fife cutter Pen Duick on his way to the first Fife festival in the Clyde, having celebrated the yacht’s 100th birthday in Benodet, Brittany – his and her home river. Tabarly was an inspirational sailor, equally at home on a high tech catamaran as he was helming the vintage classic 15-M Tuiga out of Monaco or at the French classic regattas – finding out how boats like that should be sailed and helping to establish the classic yachting scene.

The centenary of Pen Duick had been a success and it widened the cause for looking after and restoring old boats. Sailors had scratched their head at the idea that a wooden boat could last that long… But Tabarly’s boat wasn’t wood anymore, she had been sunk by his father during WWII to hide her lead keel from the Germans, who wanted lead for bullets, and after she was raised Tabarly always knew she would have to be rebuilt. He eventually covered her hull in glassfibre, and then removed the timber from inside. She still has a wooden deck, and sails as she did; he made a very good job of it, and perhaps most importantly, she looks the same – so like your grandfather’s mallet that has four new heads and three new handles… it’s still his mallet.

Soon lots of old boats were being restored, many in like-for-like wood. And they could be raced again… And of course Wm Fife boats were at the top of the list for restoration. Fife’s designs always were considered among the most beautiful boats ever built. And they are still able to capture the heart of a sailor. But these Scottish and English boats were being restored and then raced in the south of France or other Med regattas. There wasn’t such a classic event in the UK. Then in 1998 marine artist Alastair Houston and his sister Fiona proposed a regatta on the Clyde – just for Fife designs. They got early support from Eric Tabarly and from Ernst Klaus who owned the superbly restored 98ft ketch Kentra… There were to be smaller boats too – the 27ft Mignon (also 100 years old) and 30ft Vagrant and Starlight… Tabarly would be sailing in company with Swede Bo Eriksson with his partner Elizabeth Carlsson and crew on Magda IV built in 1904 and still original! One of Fife’s last boats Solway Maid was to be there, as was the 72ft schooner Elise (now being restored at Joe Irving’s yard on the Humber) and of course the utterly gorgeous 102ft sloop Moonbeam… a boat designed to slide through your dreams, like an architectural working work-of-art, connecting you to another world: a world of Olympian fascination with the sea, Edwardian sensibilities and pre-First World War innocence.

All this was promised as Tabarly left the French coast and cruised north with five French crew via Cornwall’s Helford River and the Lizard, where so many Atlantic sailing records were recorded, and the charming small fishing port of Mousehole, . They had sheltered in Newlyn and were held there by Northerlies for a few days. “I was never held such a long time in port!” Eric had complained. Eventually on 12 June 1998 the wind backed to the south and they could leave that morning. There was no forecast of bad weather.

Pen Duick left port with Magda IV which was under reduced sail as she can be a wet boat. Eric set every sail he had from her grand high-peaked gaff mainsail and topsail plus a couple of jibs. He was rounding Lands End within two hours. He could keep in touch by handheld VHF but the two boats had lost contact by 9pm that evening.

The wind freshened in the afternoon with Eric in his usual style, handing the topsail and the jib. At 66 he was super fit and worked on the end of the bowsprit without lifeline or lifejacket… as a sailor of the old school he had said he would prefer an hour in the water to being tied on… so there were no jackstays on Pen Duick.

But in the Irish Sea a strong latent swell remained from the days of northerlies and now the southerlies were creating a nasty chop across the top of them. The going became uncomfortable on a boat with such a low freeboard and Eric decided to reef, with first one and then two reefs in the main. Just before midnight the boat was still overpressed with just her reefed main and jib. The night was now black with thick rain and the following sea had risen with the wind regularly gusting F6 (over 22 knots). Those on board estimated the seas had risen to three or four metres and they were steep. Eric’s plan was to douse the main and hoist the storm trysail – a small steadying sail. The boat was surging ahead at nine knots on the gusts of wind but also rolling from rail to rail like a metronome. The boom needed to be sheeted into the centreline and then the gaff brought down on its two (peak and throat) halyards. If you don’t have double topping lifts (a line from the mast head to the either side of the end of the boom, the gaff is free to swing out to the side. On Pen Duick this would have been a delicate manouevre in a force four; with her stern to the weather like that, many a skipper would have brought her up into the wind though in these conditions she could have turned into a bucking bronco with possible breakages of gear.

How it Happened

With two crew by the mast to bring down the gaff and a third holding her course, Eric is standing on Pen Duick’s deck with his chest against the boom fighting to control the sail and get a line around both boom and gaff to secure them. It’s something he’s done a thousand times but in a wild roll the gaff swings out violently to starboard and comes back to strike him squarely across the chest. Its massive force propels him backwards and clean over the side of the yacht into the sea. The crew hear him shout something before he is lost in the night. He has no lifejacket, no torch no baby rockets. The personal EPIRB hasn’t even been invented.

Liferings are immediately thrown into the sea and red distress rockets fired. But being some 35 miles off the coast of SW Wales and now 80nM north of Lands End there’s no chance the little handheld VHF will be heard. And there seem to be no boats nearby. Worse still they have sailed a way downwind before being able to lash the sails to the deck, start the engine and turn around to return to the spot of the MOB. The engine is just a few HP, and with its two-bladed prop it was only designed to get in and out of a marina; Eric liked to do everything under sail. Now it seems useless – it takes them three hours to get back to the spot where he went in the sea. After hours of searching, and it now being nearly daylight with the wind calmer, they turn towards the coast to find help. Soon they spot a maxi yacht, Longobarda, belonging to Mike Slade who is sailing to Ireland. With the VHF battery exhausted they set off a flare and are relieved when the yacht alters course to come alongside at 0700.

The night’s tragedy is shouted across to the modern boat, which promptly alerts the Coastguard. Several ships and an RAF helicopter, the lifeboat and a Royal Navy minesweeper join the search. Pen Duick eventually makes port at 6pm that evening where her crew are joined by those from Kentra and Magda IV.

Eric’s body is not found, until weeks later.

Fifes – a regatta like no other

A few days later Pen Duick is sailed north to be in the Clyde for the Fife regatta from June 19 – 24. The French press are crowding the little marina at Largs with TV vans where Madame Jacqueline Tabarly, Eric’s wife, comes sweeping down the pontoon to see her. The death marks the regatta with a sombre note but it does not overshadow it, the sailors are quite sanguine: “the sea has taken one of its own”. They also knew that Eric would have loved this regatta for its purpose in honouring the boats, their designer and the crews, skippers and owners who keep them going. So they toast him – with rum, with beer, with wine.

On the Monday of the regatta the boats are racing up the Clyde while back in France they are holding a state funeral; laying a wreath from a warship in the Rade de Brest where Eric’s other Pen Duick yachts are at anchor in salute.

And despite Eric’s loss the regatta was a huge success. It was a minor miracle to get the large yachts out of the Mediterranean and north into the alternately brooding or shimmering waters of the Clyde. There was another regatta in 2003 and in 2008 and then in 2013 and Kentra has been at all of them. The regatta moves from Largs to Rhu to Rothesay with excellent racing and the most extraordinary parties, at Kelburn Castle, the Royal Northern and Clyde Yacht Club and the neo-gothic stately treasure Mount Stewart House on Bute. For sailors with any interest in Fife, or classic yachts, it has been the closest thing we have to a pilgrimage – the sailing itself being like a final act of homage, to those great boatbuilders who launched yachts that will still make the heart yearn.

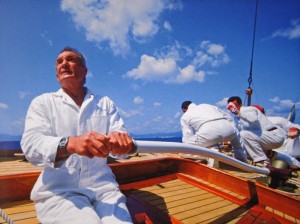

From notes by Christian Février interviewing Erwan Quéméré, photographer and Pen Duick’s helmsman on the fateful night. Top photo: Pen Duick

This year there is not a Fife regatta but there are many who hope that it will come again.

It was after a month, on July 20, that a trawler found Eric’s body in the Irish sea. And while it’s impossible to say what he could have achieved if he had survived, it’s certain that it would have been great, like the rest of his extraordinary life. For those who speak French there is a fabulous film on Tabarly by Pierre Marcel, with a superb sound track by Yann Tiersen. Trailer below.

As a learning point how could Tabarly have made this manouevre safe? Without being there it’s extremely difficult to say. And it feels churlish to question the exercise.

But when things are difficult with leaping gear, one way to douse sail like this when running downwind on a gaffer, is that you need to snuff the gaff to the boom with a coil of rope, going around both spars from the mast moving aft – ideally with the boom tied down securely first to a strong point on the deck. This means getting the sail down fully before you start to wind the rope around the spars, and there is danger in the sail being in the water, but with the boat moving forward it should be less of a problem than a swinging gaff. Or is there a better way?

Points on seamanship are always welcome – email editor@classicsailor.com