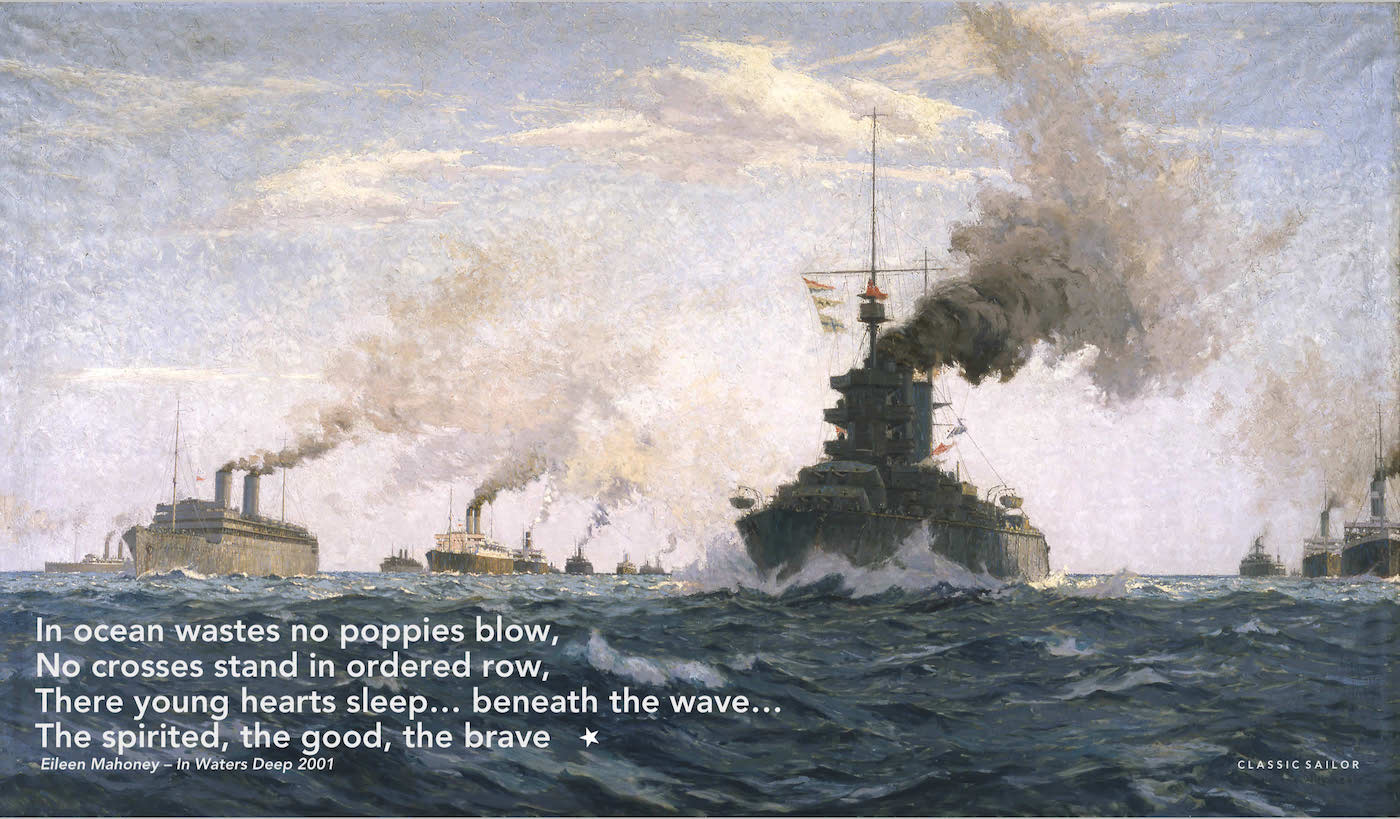

On the 100th anniversary of the Armistice of WW1, Eileen Mahoney’s poem In Waters Deep,

conveys the loss of so many sailors killed during the conflict

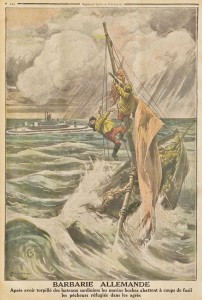

Eugene Damblans’ illustration for the French Petit Journal shows German “barbarity” as U boat sailors shoot the fishermen of a torpedoed sardine trawler out of the rigging (May 1917)

An oft-unsung service, were the convoys of merchant seafarers who kept Britain supplied, as well as fishermen who carried on as best they could despite the threat of mines and U-Boats. An estimated 14,661 merchant seafarers were killed during the first world war, after which King George V officially named the service as the Merchant Navy.

The Royal Navy suffered greater losses in WW1 (1914 – 1918) with an estimated 44,000 seamen (and women) killed

(6,000 died at the Battle of Jutland in 1915 alone) but many in Britain have been appalled that it was not until

the year 2000 that the Merchant Navy were represented as an official service in Cenotaph commemorations.

The Merchant Navy war memorial is at Trinity Square, on Tower Hill, London designed by Sir Edward Lutyens in 1928.

A second memorial in the same place commemorates the dead of World War II (1939 – 1945) which were significantly greater,

reflecting the menace of the U-Boat fleet and the fact that Merchant vessels were not a target for the Germans in WW1 unless

they were armed (see note below). Conservatively 36,749 seamen and women were lost by enemy action in

the merchant fleet, compared to the Royal Navy’s 50,758 men killed in action plus 820 listed missing. Horrifically

over a quarter (27%) of the total number of merchant sailors lost their lives during World War Two – a huge figure compared

to an average of 3.3% from the other services – army, navy and air. Many of these Merchant Navy dead were from the

Commonwealth and other nations and several (50 or so) were women – serving in various roles on the passenger ships and liners.

Eileen Mahoney’s poem In Waters Deep

sums up the loss of sailors during wartime

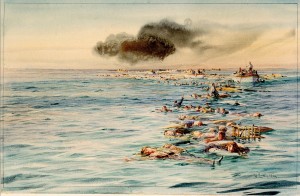

Track of the Lusitania by Wm Wyllie. The 787ft / 240m British ocean liner had been the world’s largest passenger ship. She was sunk on 7 May 1915 by a German U-boat 11nM off the south coast of Ireland with the loss of 1198 passengers and crew, 128 of them American civilians. There were 761 survivors. Britain and America regarded the sinking as a war crime.

In ocean wastes no poppies blow,

No crosses stand in ordered row,

There young hearts sleep… beneath the wave…

The spirited, the good, the brave,

But stars a constant vigil keep,

For them who lie beneath the deep.

‘Tis true you cannot kneel in prayer

On certain spot and think. “He’s there.”

But you can to the ocean go…

See whitecaps marching row on row;

Know one for him will always ride…

In and out… with every tide.

And when your span of life is passed,

He’ll meet you at the “Captain’s Mast.”

And they who mourn on distant shore

For sailors who’ll come home no more,

Can dry their tears and pray for these

Who rest beneath the heaving seas…

For stars that shine and winds that blow

And whitecaps marching row on row.

And they can never lonely be

For when they lived… they chose the sea.

©2001 by Eileen Mahoney

Note: In WW1 the warring factions agreed not to target mercantile vessels at sea – treating them as civilians in the conflict. Looking at the lists of British trawlers and other merchant vessels sunk at the enemy hands it’s hard to believe this was taken seriously across the German Naval command, but nevertheless the sinking of the Lusitania was viewed as an egregious act of German violence by the Allies, though at the time Germany contended that the ship was carrying military supplies and ammunition being transported to the Western Front, and therefore was a legitimate target. After the sinking the Germans agreed to restrict their U-Boats from targeting merchant ships unless they were obviously armed and especially passenger ships. But as the war of attrition in the trenches escalated this policy loosened and in March 1916 a passenger ferry, SS Sussex, was torpedoed in the Channel and severely damaged. Around 50 people were killed causing America to put pressure on the Germans who gave an agreement known as the Sussex Pledge. This guaranteed passenger ships would not be sunk, merchant ships would not be sunk without confirmation of weaponry aboard, and German provision would be made to rescue the crew of a torpedoed ship.

The Germans however soon revoked the pledge with U-Boat action resuming against merchant vessels in the North Atlantic. This antagonised America which then entered the war in April 1917.

For more detail on British Vessels Lost at Sea, 1914–1918, published by HMSO in 1919 see:  HERE

HERE

Main image: English marine artist Norman Wilkinson painted Canada’s First Contingent leaving Canada in October 1914. Over 32,000 Canadian and Newfoundland soldiers sailed to Britain in 30 passenger liners. At the time, it was the single largest group of Canadians ever to sail from Canada.

[…] As a Sailor, I would be remiss if I didn’t include this one as well from Eileen Mahoney In Waters Deep […]