It’s something we should all practice – just in case the engine does not start. So how do we prepare to anchor under sail?

By Trevor David Clifton

Rolling white horses were thumping into the port bow sending showers of salty spray across the cockpit and down our necks. But it was summer with the sun shining so it was fun. We were fine-reaching across Christchurch Bay, aiming for Poole.

At the outer marks of the approach channel we bore away and cruised towards the entrance.

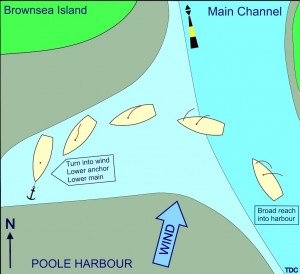

Our plan was to anchor for the night in a little creek, south of Brownsea Island, about a cable WSW of the easterly cardinal that’s dead ahead as you come in.

“OK, start the engine.” I said.

It wouldn’t start.

Things are different in the confines of a river or creek where your approach direction and manoeuvring space are restricted

by the banks or shallows

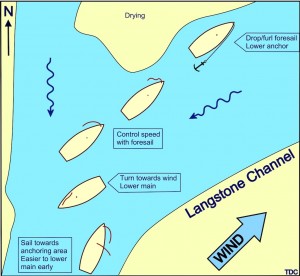

We sailed in with the wind on the port quarter, but it would be fine on the port bow for the final approach to the chosen spot (Fig 2). We furled the foresail as we changed course, so foredeck crew wouldn’t have to put up with a sail and sheets flapping around.

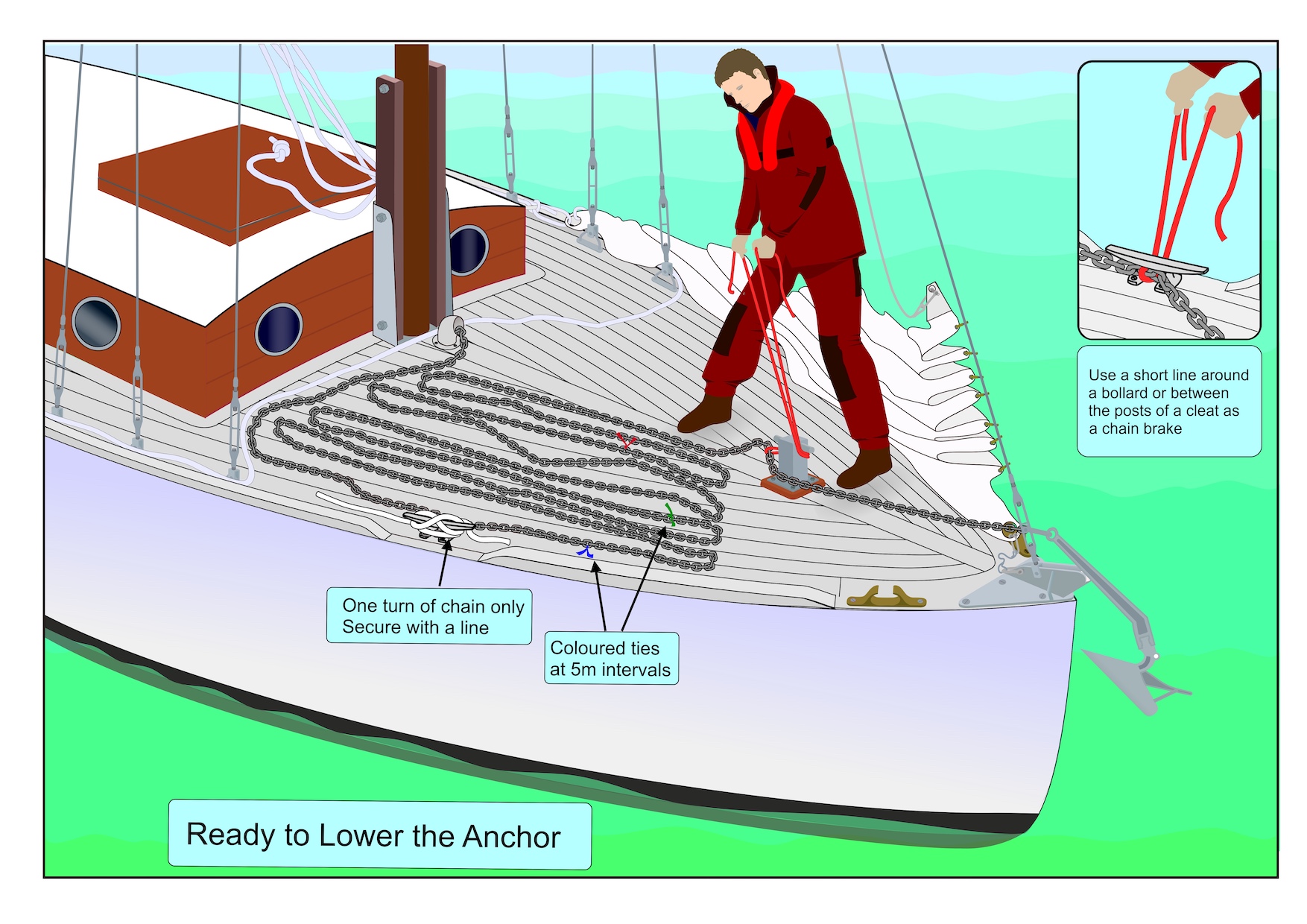

The sea bed is mostly mud, and I’d checked the depth so we knew how much chain we needed (Fig 1 above)).

The boat, like many, didn’t have an anchor winch. We hauled up the twenty metres of chain, laying it out – flaking it, on the deck in four-metre bites. I checked the shackle connecting the chain to the anchor, took a single turn around a cleat near the twenty-metre mark, and secured it with a short line. We rigged a ‘chain-brake’ (see main image above) around the bollard on the foredeck.

When all was ready, we part lowered the anchor over the bow roller, holding it in place with the brake we’d rigged.

Anchoring Under Sail Fig 2: Poole Harbour

“OK,” I said to the helmsman, “Head for that post,” pointing to a green post dead upwind. “Call out the depths as we go.”

We lost way.

As the boat came to a momentary standstill the anchor crew let the brake off and the mainsail halyard was released. The chain rattled out – still under control – and the main came rattling down.

The bow blew off downwind a little until a gentle tug on the chain told us that the anchor had dug itself in. Suddenly all was steady and comfortable.

We snubbed the anchor chain, tidied up the mainsail, hoisted the day signal and made a cup of tea.

Then I tackled the engine.

If you sail a boat with an engine, one day it won’t start. Water in the tank, air in the fuel system, flat batteries, rope around the prop – they all happen.If you’re at sea and there’s no mooring or pontoon handy, then abandoning ship or drifting around the ocean for ever are your only options, unless you anchor. Of course you could sacrifice your independence (pride?) and call for help!

Trading schooners in the Pacific used to (still do?) sail downwind into a lagoon, drop the anchor, literally, and swing around to lie to the wind. Some very experienced sailors advocate anchoring on the run but, unless there’s no other option I would always choose to anchor close to a weather shore, so my approach will almost always be upwind (Fig 2). I just don’t fancy sailing downwind into a shoal of anchored boats!

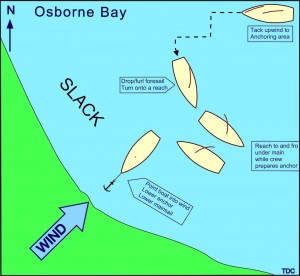

Fig 3: Osborne Bay – slack water; anchoring into the wind

I find it easiest to sail close-hauled to the chosen anchorage, with foresail and main still drawing, then adopt the sailplan that tide and wind dictate. Take Osborne Bay for example, probably the most popular anchorage in the country. The shoreline there is roughly SE–NW, left to right as you look at it from seaward, so pretty-well at right angles to the prevailing wind direction, which may explain its popularity.

In a south-westerly, at slack water, (Fig 3) my approach would be as described above. Close to the shore the water will be reasonably flat so the crew will have a clear, level platform to work on. We can safely reach back and forth under the main if the crew is bit tardy organising the ground tackle.

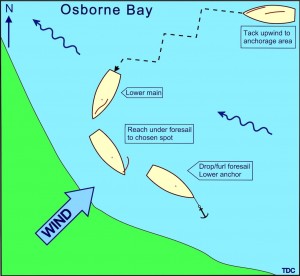

Fig 4: Osborne Bay – tide ebbing; anchoring into the tide

When all is ready the boat is pointed into the wind and, as she slows, almost to a stop, the anchor is lowered, fairly quickly but not so quickly that the chain ends up in a heap on top of the anchor. The main must be lowered fairly quickly too before the bow blows off too far and the sail fills again. When the anchor bites the boat will be held into the wind and all should be well.

If there’s a tide running the final approach would be different, the tidal flow there is roughly parallel with the shore. With the wind still coming from the south-west we could reach on a port tack into a rising tide or on starboard into the ebb. But it wouldn’t be easy to get the main down on this point of sail so we’d do it under foresail. The inconvenience to the crew would still be minimal because the main body of the sail would be somewhere outside the guardrail. (See Fig 4)

But when the wind or tide changes so does the plan.

Things are different in the confines of a river or creek where your approach direction and manoeuvring space are restricted by the banks or shallows.

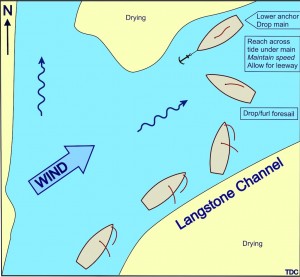

Fig 5: Langstone Harbour – wind over tide; using foresail only

In wind over tide conditions the boat’s forward speed can be controlled using just the foresail, and the bow can be brought up over the spot where the anchor is to go, unless the wind is so light that the tide is the more powerful, in which case you probably wouldn’t have sailed into Langstone harbour anyway!

If the wind is more than a zephyr it will push the boat forward over and beyond the anchor, while the current will

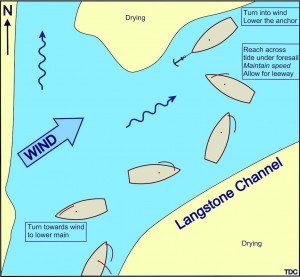

Anchoring under sail Fig 6: Langstone Harbour – wind with tide; using mainsail

determine the direction she faces (See Fig 5).

The trickiest situation to deal with is when the wind is with the tide, when you have to sail close-hauled just to stand still. A bit of careful judgement is needed. Which course of action you choose will depend on the slant of the wind and how familiar you are with the boat’s handling characteristics. There are three main options… and the potential for a snarl-up in all three!

You could fine-reach across the tide under main or foresail (or both), then ‘luff-up’ so that the boat heads into the wind and tide at the spot where you wish to put the anchor down (Fig 6).

The danger here is sailing too close to the wind, stalling and the bow being blown off. If this happens there is every chance that the wind will fill the sails and drive the boat forward. Then the only escape option is a very quick gybe (which suggests that undertaking this manoeuvre might best be done under foresail (See Fig 7) – if your foresail is big enough); if there’s not a lot of room you could be aground very quickly.

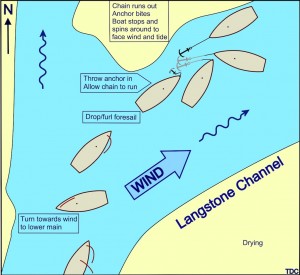

A third option is sometimes known as ‘Crash Anchoring’. This too has potential for disaster. Fig 8 shows the manoeuvre fairly clearly.

Fig 7: Langstone Harbour – wind with tide; using headsail

Fig 8: Langstone Harbour – wind with tide – crash anchoring

So what can go wrong?

As the boat sails past the anchor the chain – which must be allowed to run out freely – will be stretched out along and underneath the hull; there is a possibility of damage to the surface and worse, the chain could foul the propeller and/or the rudder. When the anchor bites the boat should be steered towards the chain to reduce the chances of this happening. The boat will swing around and point towards the tide. The sail can then be dropped/furled.

And what if the anchor doesn’t bite? The boat is likely to be drifting with wind and tide, slowed a little and, hopefully, kept at least partly head-to-wind/tide by her dragging anchor; it shouldn’t be difficult to haul it back on board. At the same time setting and backing a small amount of foresail might help to point the bow in a safe direction and keep you off the putty. Then you can try again!

There is a fourth option: find somewhere else to anchor!

POINTS TO NOTE

1 In real life it is unusual for conditions in a sheltered anchorage to be bad enough to cause problems, nevertheless it’s worth practicing on a gentle day just to get the procedure right.

2 Wear gloves.

3 Don’t get your fingers caught between the chain and a deck fitting.

4 Make sure that the chain is secured at its inboard end.

5 If you’ve never done it before try the brake I’ve illustrated where there’s plenty of room, not because you’ll need the space but so that you don’t have to worry about other boats.

6 Don’t say ‘Drop the Anchor’ unless that’s what you want to happen, in gentle conditions the chain will end up in a heap on top of the anchor!

7 An anchor chain running out over the deck makes a lot of noise but doesn’t normally harm the deck or fittings; and it will run over a sheet or through the ‘brake’ without ‘dragging’ the rope.

8 Once a boat loses way the bow will be ‘blown off’ by the wind; how quickly that happens depends on her weight and underwater profile; if the mainsail is still up it can fill with wind and drive the boat off in a direction you may not wish to go!

9 Once you’re safely at anchor hoist the day-shape and/or turn on the anchor light; identify some landmarks so that you can see if the anchor drags; if appropriate pick one or two that will be visible after dark.