The summer of 1939 would be the last chance for several years that yachtsmen could take extended cruises to places like the Baltic. Author Julia Jones relates how her father sailed to Poland in the weeks before Germany invaded, and on his return found his services already required by the Royal Navy. Two days later, on September 3 1939 – and the same day war with Germany was declared, he joined HMS Forth in Rosyth.

On September 3rd 2019 I had the perfect invitation – I was asked to talk about George Jones’ (my father’s) book, The Cruise of Naromis, to members of the Little Ship Club in London.

The Cruise of Naromis is the slim volume I was able to make from my father’s 1939 diary, a suitcase of somewhat random photographs and papers from his wartime RNVR (Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve) service and the account he wrote of his trip to the Baltic in August of that year. My father was 21 years old and had already volunteered with the RNV(S)R, known as the ‘Yachtsman’s Reserve’. When he returned home on Sept 2nd he found that his call-up papers had already been waiting for a week.

Initially I had thought this small book would only be of family interest – in fact many people have found that it has prompted them to look back into their own parents’ and grandparents’ WW2 experiences. Others are interested because they hadn’t known about the RNV(S)R. I’m continuing my research into this group of volunteers and would be very glad to hear from anyone else with knowledge to share.

On September 3rd 1939 therefore (the day Britain declared war on Germany), my father was hurrying north to join the submarine depot ship HMS Forth at Rosyth. The Forth was a floating workshop, a hotel, an operational centre. She had a crew of over 1,100 men, displacement of 8,999 tons and was armed with 16 AA guns. Quite a contrast with the trim little pleasure yacht he had just left.

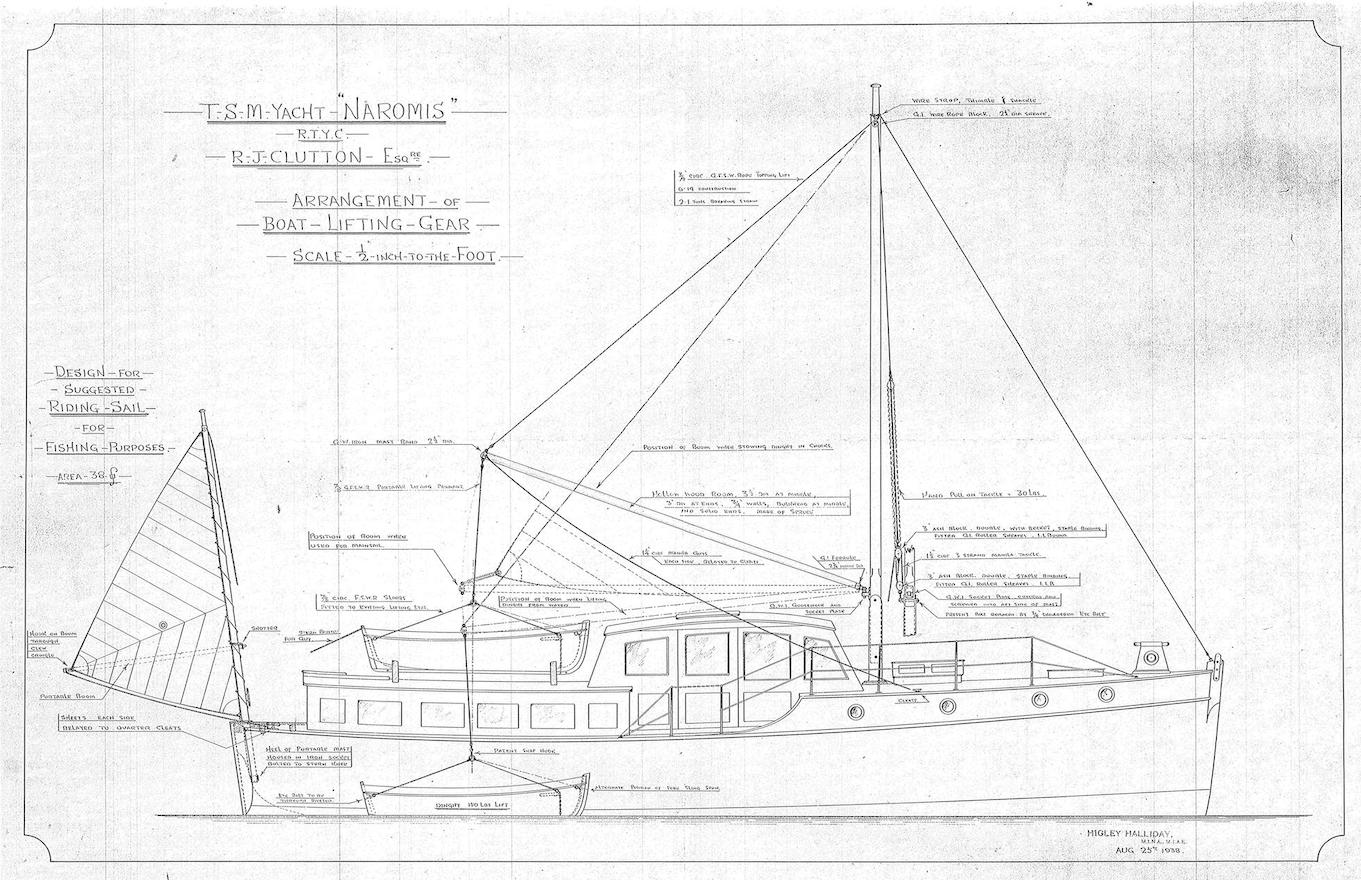

Both vessels had been launched during 1938 but whereas HMS Forth had been built by the internationally famous John Brown shipyard on Clydebank, Naromis was a product of the Norfolk Broads. Her designer, ‘Higley’ Halliday (Edmund Walter), was a founder member of the Little Ship Club, established in 1926. The club was part of a movement to establish better facilities and training for yachtsmen and to open up the sport to a wider range of people. ‘Bachelor girls’ were welcome. Some of these early Little Ship Club members might have been among the hundreds who had already bought Yachting on a Small Income by another of the Club’s founders, the newly-appointed editor of Yachting Monthly magazine, Maurice Griffiths. By the time my mother’s read-to-pieces sixpenny reprint copy was published (c1939-40) these hundreds had teemed into thousands.

In his introduction to the new edition Griffiths looks back to the 1920s: ‘There was a time when a man who owned a small boat brought her into the conversation on every conceivable occasion referring to her with loud nonchalance as “my yacht” or else avoided all reference to anything that floated for fear his acquaintances might imagine he was secretly wealthy and try to borrow £5.

‘When this little handbook was first published in 1925 the Public at large – and that means the “man in the street” – thought of yachts solely as those expensive white things that fluttered around in the Solent and cost someone hundreds a year to run. Nowadays, such has been the publicity of the Yachting Press and even of the Daily Press in reporting round-the-world voyages in small sailing craft by bank clerks, shop assistants and the out-of-works, that the possibilities of spending thoroughly enjoyable weekends and holidays afloat and in one’s own little floating home on even a bank clerk’s salary have become more widely known.

Griffiths goes on to talk about the continuing improvements in facilities of yachtsmen, including the Little Ship Club, where Higley Halliday had become Chief Seamanship Instructor. There’s a (newly added?) chapter on The Feminine Owner’ ‘Your joining a yacht club will probably result in your being introduced to others like yourself who are keen to sail but have not the nerve to go it alone.’ This, Griffiths concludes ‘is now the day of the Little Ship and as every year passes her numbers increase like a penfull of rabbits.’ Hmmm, I thought, as I read this… My mother bought this book: subsequently (1946) she decided to follow Griffiths’s advice and buy a boat. In so doing she met my father – by then a yacht agent. That resulted in myself, my two brothers and (at my most recent count) NINETEEN small, medium and very small ships in our family… so who needs rabbits?

On September 3rd 1939 however my mother, aged 15, was in church with her mother. She remembered the vicar sharing Chamberlain’s 11.30am announcement and then her mother’s desperate haste to get home to her husband and their family of boys. My grandmother had been a Red Cross nurse in the First World War; she would have felt a justifiable horror what might be about to happen to her family now. Almost all except the youngest children did serve, but their WW2 service was different from their WW1 father and uncles – the majority were with the RAF, mechanised regiments or, in one case, survived the BEF to join a commando unit. Mum was in a munitions factory and a branch of the Foreign Office where they were doing something so secret she never quite worked out what it was, except that it was in some way connected with Bletchley Park and her job was to make the tea, do the filing and ask no questions.

At the Little Ship Club on September 3rd 1939 many members would be expecting a similar call-up to my father. As the prospect of war had come closer – particularly after the 1938 Munich crisis – and the shortage of trained men for the navy became more apparent, experienced yachtsmen had been invited to volunteer for a supplementary branch of the RNVR, the RNV(S)R. Maurice Griffiths was a member. There was however no training provided – volunteers were expected to organise (and pay for) their own. The Little Ship Club, with Chief Seamanship Instructor Halliday, had stepped into the breach providing hundreds of hours of instruction to members and non-members. When war came Halliday (born 1875 so too old for active service) was co-opted in to the Special Branch of the RNVR and asked to carry on his good work.

My father’s trip on Naromis was probably intended as RNV(S)R ‘training’. Someone from the London Division had got in touch not long after he volunteered: ‘Crocker suggests I go to Danzig and pay 9 gns.’ (Diary 1.8.1939) Danzig (Gdansk) was not, however, a place where you’d want to find yourself in September 1939. The German Battleship Schleswig Holstein had arrived there on a ‘courtesy visit’ on August 26th – by which time (fortunately for my future existence) Naromis had been escorted out of German waters by a mine-layer and was hurrying home via Sweden and Norway. Early in the morning of September 1st the Schleswig Holstein opened fire on the Free City and German troops poured across the Polish border. Naromis, meanwhile, having travelled 1300 sea miles in 3 weeks without mishap, ran aground on a beach in Yorkshire: ‘It had one saving grace, a well-built pub. It was here that we heard the news of Germany’s attack on Poland and the phrase: “German troops moved across the frontier at dawn” that was to become so well-known during the next twenty months.” (Naromis p 91)

Not everyone in my audience at the Little Ship Club on September 3rd 2019 had made the connection with Sept 3rd 1939. That’s understandable as we all have our personal significant dates. But where were your parents – or grandparents – on September 3rd 1939? And what happened to them next?

Main picture Naromis‘ sailplan. Note the dinghy lifting arrangement with her boom. Julia Jones has authored several books on sailing including stories to inspire children to sail in her Strong Winds series. George Jones survived the war and went on to found the East Coast Yacht Agency – the well-known Easy Cosy, at Woodbridge on the River Deben in Suffolk.