Dividing the earth; meridians and parallels and how they can be used to pinpoint any locations. Degrees, minutes and the Nautical Mile. And how the grid scale on a nautical chart uses these measurements to enable the navigator to judge distances

By John Clarke, Principal of Team Sailing

The globe divided

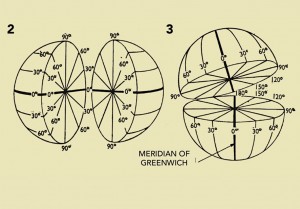

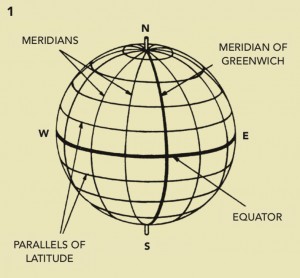

For navigational purposed the earth has been drawn as shown in figure 1.

Charts use Latitude and Longitude, because we need to know where we are on the featureless surface of the sea. Therefore they have the Latitude and Longitude grid printed on them.

And there needs to be a start point for determining the latitude and longitude of a particular point.

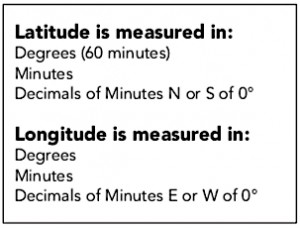

For latitude it is the Equator, and points are defined as being north or south of the Equator. Zero degrees for points on the Equator, and ninety degrees north or south for points at the north or South Pole.

For longitude it is the line running north or south which runs through Greenwich (see the opposite page to discover why Greenwich was used), and points are defined as east or west of the zero-degrees Greenwich meridian.

So, to determine a position on the earth it is simply necessary to see how far north or south of the Equator, and how far east or west of the Greenwich meridian the point lies. And they are measured in accord with figures 2 and 3.

Defining distance

From figure 1 it will be obvious that as the lines of longitude aren’t parallel you cannot use the difference between these lines to measure distance, when you want to plot your position at sea.

Very close to the North Pole (or South Pole) the distance between say 10 degrees west and 20 degrees west is tiny, whereas very close to the equator it is probably something like 600 miles.

But if you look at the lines of latitude in figure 1, you will see tthese are parallel, so the distance between say 10 degrees north and 20 degrees north; and the distance between say 40 degrees north and 50 degrees north is the same. Thus we can use degrees of latitude to measure distance on a chart.

The measurement of distance is internationally recognised as the Nautical Mile (nM). (At approximately 2026 yards it is 1.15 the length of the statute mile, or 1.4 Kilometres.)

One degree of latitude is equal to 60nM, and one minute of latitude (one sixtieth of a degree) is equal to 1 nM. Being able to measure distance in degrees of arc over the earth’s surface is why sailors and airmen use the NM as opposed to the statute mile, which is a purely arbitrary measure of distance. Having this handy grid scale at the side of the chart means you can instantly judge distance, in any direction, in miles or fractions of a mile from your chart using any handy measuring tool – such as your thumb; invaluable on a heaving chart table (and a possibly heaving navigator).

Mercator projection

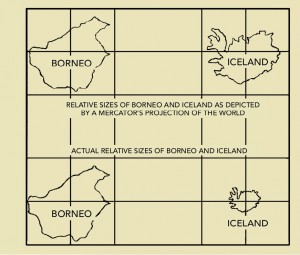

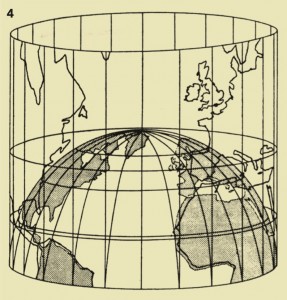

There is a problem though for navigators in representing the three dimensions of the earth on a two-dimensional surface, and this has been overcome in different ways. The one which most sailors are familiar with is the Mercator Projection.

If you look at figure 4 you will see how it works. The earth is made rectangular. Now there are two effects from this.

Firstly, it makes objects nearer the North Pole look bigger than they are, see the diagram below comparing Borneo and Iceland.

And secondly it makes the lines of latitude more spaced out the closer you get to the poles, (this is why when you are measuring distance you must measure off the latitude scale close to where you are).

And there is one important drawback of this type of chart – it is accurate only up to a range of about 600 nM, fine for sailors but those who deal in bigger distances need to use different types of chart, outside the scope of this series of articles.

Next month we’ll be looking at how to measure using a chart and explain about variation and deviation. ★

Why Greenwich?

Greenwich has been the universally-adopted Prime Meridian – the zero-degree line of longitude from which all others are calculated – since the 1884 International Meridian Conference in Washington; before that pretty well all seafaring nations had their own Prime Meridian, often passing through the capital city, but most charts, even those published by other nations used Greenwich as their prime, largely because most seafarers used the British Nautical Almanac, first published in 1767, to calculate their positions.

Other work centred on the Royal Observatory enhanced Greenwich’s status, notably the Board of Longitude (1714) set up to find a reliable method of discovering longitude at sea, and eventually, in 1765, recognising John Harrison’s chronometer. The timeball on top of the Royal Observatory, designed to be visible to ships on the Thames, was set up in 1833. ★

Our brief history of Mercator can be found: HERE